“The friction of contradictions fire the crucible out of which Northampton community formed.” This sentence is how historian Kerry Buckley introduced Historic Northampton’s 2004 update of the city’s story, A Place Called Paradise. ”The dynamic between factions_ newcomers and old-timers, Yankees and immigrants, young and old, has always been part of the creative tension that, at its best, has enlarged the community’s capacity for tolerance.”

Add LGBTQ peoples to Buckley’s list of contrary factions. LGBTQ peoples in large numbers came to, or came out within, Northampton starting in 1970, creating friction both in the town and amongst themselves. Peoples, in the plural, because it has been successive waves of differently-identified persons who have emerged, come out, gathered, organized, agitated, advocated, and created on their own behalf. There have been multiple peoples over more than four decades, with little in common except an outlaw status — outside heteropatriarchal marriage (until 2004) and stigmatized — that has formed the basis for occasional coalition and a more mythical community.

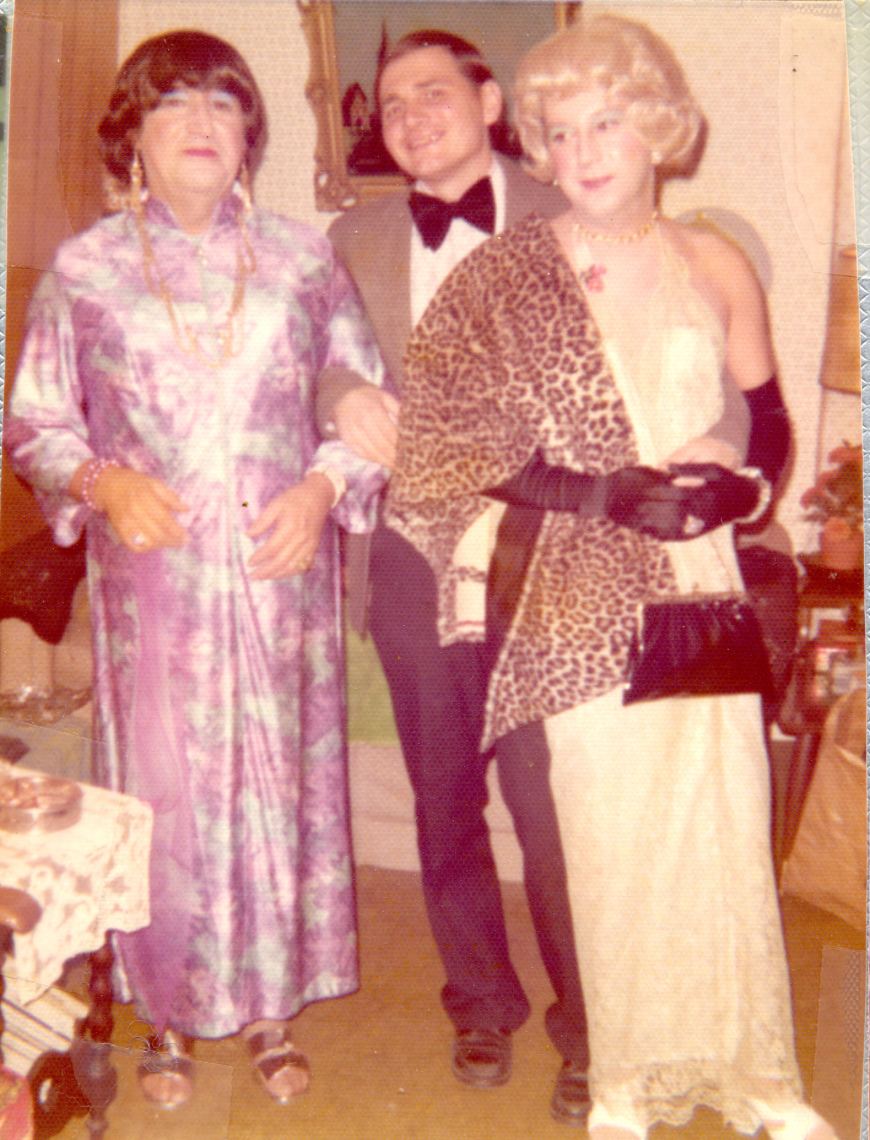

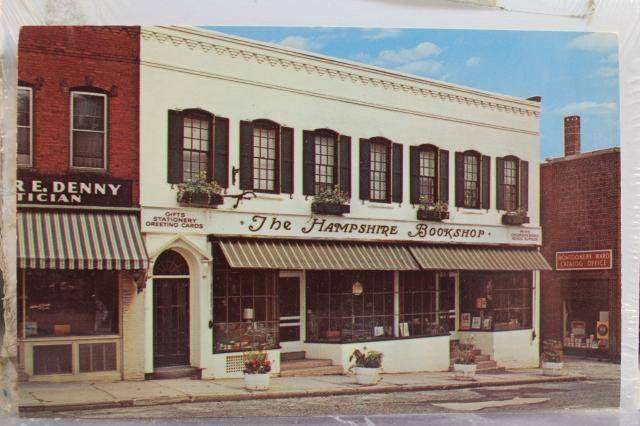

LGBTQ people were here in Northampton all along, just not visible until starting in the 1970s various populations, sequentially, came out to each other swelling to a critical mass that allowed for organization. Lesbians; then gay men; then their parents; add queers and bisexuals, here come transsexuals, and transvestites; don’t forget young people; how about spouses or significant others? Each newly emerging group defined themselves, voiced their needs to each other, and added unique solutions to respond to those unmet needs. Each group spun themselves into the fabric of a subculture that gradually became more visible on Main Street. Chief among the needs for each group of people have been safe and supportive ways to meet each other, and, as increasing numbers of people came out and met, new groups or activities formed to meet increasingly specific needs.

Collectively (and fractiously) growing in strength over time, the activity centered in Northampton often provided an organizational nexus for all of Western Massachusetts. The long-lived and most visible LGBTQ cultural institution, the annual March/Parade (under varying names), began as a coalition for change in Northampton, reflected the shifts in politicized populations over time, and became a forum of expression for all of the region. As part of a state and national movement of change, a loose alliance of groups centered here helped bring new civil liberties in the state as well as inclusion in the politics of the municipality.

Some would say an integration of sorts has been achieved by these LGBTQ peoples, with many needs now met by mainstream institutions, and visibility largely unremarked upon in most parts of town. There is a record of groups forming and then falling away over time, but was that because they were no longer needed? The reasons for this could be explored in this blog, as well as a search for any lessons about creating change that can be applied to this new era. And still to be painted is a portrait of Northampton LGBTQ (add the latest initial) today, to hold up in comparison to that of the 1960s isolation. What has stayed the same? What has changed? What still is needed? Who is going to create something to fill that need? And can history hand them some tools to do it with?

COMING NEXT: An Overview of the 1970s.