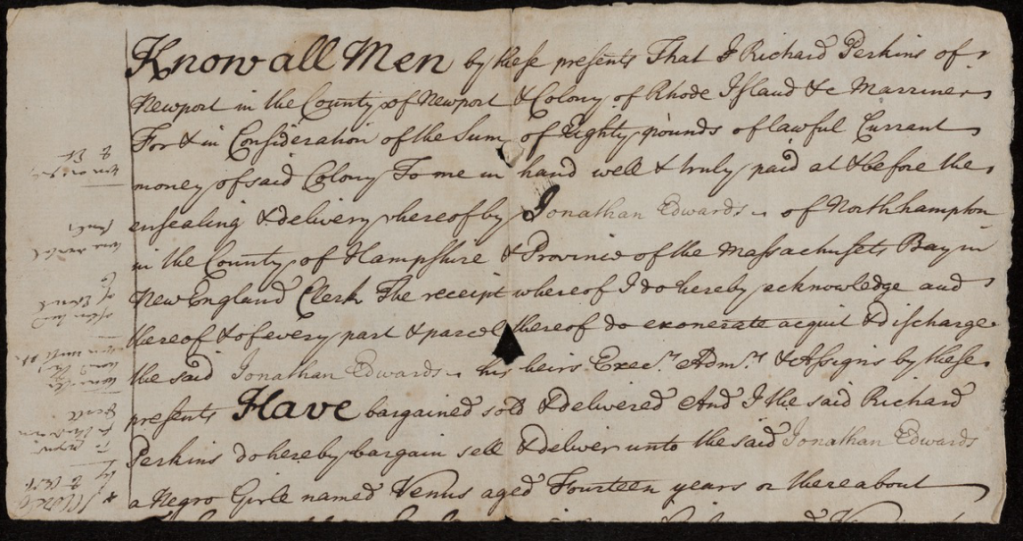

Venus Bill of Sale

As mentioned in the latest post Slavery in Northampton, the town’s minister Jonathan Edwards went to Newport, Rhode Island and purchased an enslaved young girl. Historic Northampton generously shared a copy of the topmost part of the bill of sale for the “Negro Girle named Venus” dated June 7,1731. Edwards, years later, cut the receipt into three strips and used the back for notes for a sermon. Used here with the permission of the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University. Transcription below the photo is by the Jonathan Edwards Center at Yale University, New Haven CT.

KNOW ALL MEN by these presents That I Richard Perkins of Newport in the County of Newport & Colony of Rhode Island &c Marriner For & in Consideration of the Sum of Eighty pounds of lawful Current money of said Colony To me in hand well & truly paid at & before the ensealing & delivery hereof by Jonathan Edwards of Northampton in the County of Hampshire & Province of the Massachusetts Bay in New England Clerk The receipt whereof I do hereby acknowledge and thereof & of every part & parcel thereof do exonerate aquit & discharge the said Jonathan Edwards his heirs Execrs Admrs & Assigns by these presents HAVE bargained sold & delivered And I the said Richard Perkins do hereby bargain sell & deliver unto the said Jonathan Edwards a Negro Girle named Venus aged Fourteen years or thereabout TO HAVE & TO HOLD the said Negro girl named Venus unto the said Jonathan Edwards his heirs Execrs & Assigns and to his & their own proper Use & behoof for Ever AND I the said Richard Perkins do hereby for my Self my heirs Execrs & Admrs covenant promise & agree to & with the said Jonathan Edwards his heirs Execrs Admrs & Assigns by these presents That I the said Richard Perkins at the ensealing & delivery hereof have in my own Name good Right, full Power & lawfull Authority to bargain sell & deliver the said Negro Girl named Venus unto the said Jonathan Edwards in manner & form aforesaid And shall & will warrant & defend the said Negro Girle named Venus unto the said Jonathan Edwards his heirs Execrs Admrs & Assigns against the lawfull Challenge & Demand of all manner of Persons whatsoever Claiming or to claim by from or under me or otherwise howsoever IN WITNESS whereof I the said Richard Perkins have hereunto set my hand & Seal the Seventh day of June in the Fourth Year of the Reign of our Soveraign Lord George the Second by the grace of God of Great Britain France & Ireland King Defender of the Faith &c

Anno Dm 1731

Richd Perkins

Sealed & Delivered in the presence of us

John Cranston

Jas Martin

Slavery in Northampton

In 1764 Northampton there were at least seven people held in slavery by prominent English colonists. Those enslaved, along with three other people, were listed as being “negroes” in that year’s King George III’s Census, according to historian James Trumbull in his two volume History of Northampton (published 1898 and 1902.) The names of the enslavers, but not the enslaved, were included. It is likely that they were from, or descendants of those from, West Africa, abducted, sold, and exported as merchandise to be resold in the British Colonies.

Three sentences about these ten Black people are the only acknowledgement in Trumbull’s 1300 page History of Northampton that the settlement practiced slavery. Aside from a few additional notes on two of these people, James Trumbull and subsequent town historians omitted mentioning this past as the institution of slavery became unpopular in this region. Robert Romer found this practice of historical erasure common in most of the local area, calling it deliberate amnesia in his history, Slavery in the Connecticut Valley of Massachusetts (2009).. It would be another one hundred years before historians began to rectify this lapse in memory.

The scope of this deliberate amnesia became most readily apparent to me when, this past year, I turned to Massachusetts: a Concise History by Richard D. Brown and Jack Tager. The revised edition was published in 2000 by the University of Massachusetts Press, Amherst. The history includes no mention of slavery until the narrative reaches the 1800s and the developing slavery abolition movement. The false impression given is that slavery was never practiced in Massachusetts. Many, now startling to me, facts about this past have been deliberately left out of historical accounts and, thus, general education.

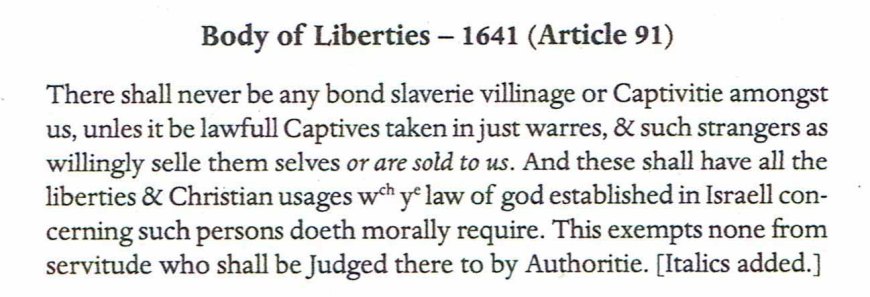

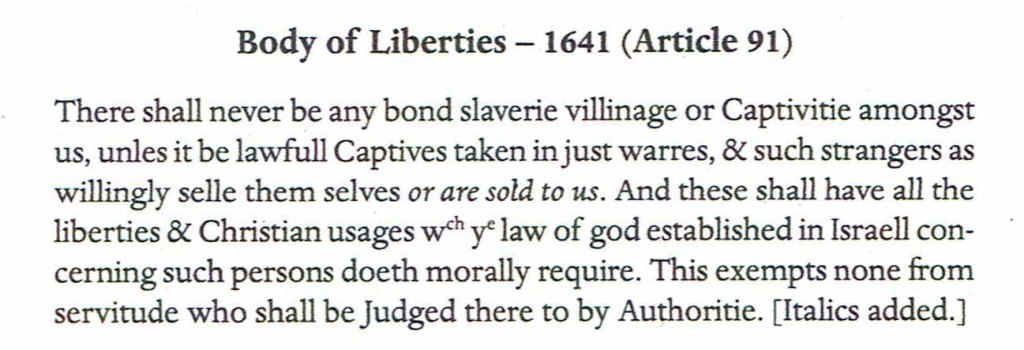

Of the thirteen British colonies, Massachusetts Bay that was the first to explicitly legalize slavery. In 1641, the General Court added an article to the Body of Liberties addressing “bond slaverie.”

Article 91 legally formalized the status of enslaved Africans who, as early as 1638, had begun to be imported and sold in Massachusetts. It also formalized the status of Indigenous people who were captured by the colonists, “taken in just wars,” and as “captives” forced to serve in English households or exported for sale as enslaved. [That is another story for later post.] These actions and the English colonists’ rationale are included in a very recently published history of New England slavery, Jared Ross Hardesty’s Black Lives, Native Lands, White Worlds (2019). Published by the University of Massachusetts Press, Amherst, it begins to fill an egregious gap in their sponsored literature.

During the colonial era, numerous additional laws were passed to control those enslaved in Massachusetts: ensuring that the children of slave women were also enslaved, regulating movement and marriage among slaves, and prohibiting black males from having sex with English women. Massachusetts Bay colony residents increasingly bought slaves, “servants for life.” Some enriched themselves as Boston, an Atlantic port, became one of the largest centers of that trade in the enslaved.

As British colonization spread from the coast up the Connecticut River Valley, so too did slavery. The English first planted themselves in Springfield, founded as a trading post in 1636 by William Pynchon. Though he is not known to have enslaved Africans, Pynchon brought with him an indentured servant Peter Swinck. According to Joseph Carvalho’s history Black Families in Hampden County, Massachusetts (2010) Swinck is the first African American known to have lived in Western Massachusetts. He later was indentured to William’s son and successor John Pynchon. The first record of enslavement in WMass is a note dated 1657 that John had paid a man for “bringing up [the Connecticut River] my negroes.” He is also known to have enslaved at least five Africans between 1680 and 1700. Springfield may have been the first Valley center of trading in the enslaved, with recorded sales made in the 1720s within Springfield and up the river valley.

The earliest mention of enslaved people in Northampton by James Trumbull concerns someone from outside of the settlement, related by him in the segment “Burning of William Clarke’s House:”

” On the night of July 14, 1681, Lt. Clarke’s house caught fire with Clarke, his wife, and grandson within. The tradition is that the door was locked from outside before the fire was set in revenge for some perceived mistreatment inflicted on the arson by Clarke. The residents escaped the log house with effort before an explosion of some combustible blew off the roof tree.”

“Jack, a slave run away from his Wethersfield CT owner was later caught and accused of the arson. He confessed to starting the fire, but claimed it began accidentally when he was inside searching for food by the light of a pine torch. Jack was taken to Boston for trial in the Superior Court. A jury found him guilty and sentenced him to be ‘hanged by the neck till he be dead and then taken down and be burnt to ashes in the fire with Maria, the negro’.”

“Maria was under sentence for burning the houses of [her enslaver and his brother-in-law] in Roxbury. She was burned alive [at the stake]. Both of these negroes were slaves. Why the body of Jack was burned is not known.”

In a footnote, Trumbull adds, “Many slaves were burned alive in New York and New Jersey, and in the southern colonies, but few in Massachusetts.”

Wendy Warren, in her history of slavery and colonization in early America, New England Bound (2016),researched this Sep. 22, 1681 execution by burning, which was the first in New England. From the trial transcript, she was able to add some details to Jack’s story. He testified that he “came from Wethersfield and is Run away from Mr. Samuel Wolcott because he always beates him sometimes with 100 blows so that he hath told his master that he would sometime or other hang himself.” Jack told the court he had been on the run for a week and a half before his capture [somewhere in Hampshire County] by a miller he was trying to rob. A Springfield court sentenced Jack to prison, but he escaped. Thirteen days later he set fire to the house in Northampton.

Earlier, in 1652, because of fires set by “Indians and Negroes,” Massachusetts had passed a law making arson a capital crime, punishable by death. Warren posits that arson was perceived as a particular threat after the conflagrations of the [Pequot] War, and the example of two major uprisings–a servants’ rebellion in Virginia and a slaves’ rebellion on Barbados. Warren wonders if the severity of the form of execution came from the English colonists’ generalized fear of conspiracy and a need to terrify any others who might imitate Maria’s actions. Jack’s body being added to her consuming fire may have been a symbolic linking of their state of enslavement and their crimes.

The challenges of controlling the lives of the enslaved didn’t discourage ownership in Massachusetts. Warren points out that, given large-scale plantation slavery never developed in New England, chattel slavery might be seen as a vanity project of the very wealthy. One such example is merchant John Pynchon of Springfield, who benefited from the increase in West Indies trade. What the wealthy had, the less wealthy also wanted. The population of enslaved Africans in Massachusetts, including the Valley, grew over the next century as increasing numbers of the more well-to-do colonists owned at least one.

From Pynchon’s Springfield, colonial plantations spread up the Connecticut River. Northampton was founded in 1654, Hadley in 1659, Deerfield in 1670, and Northfield in 1673. Over the next century, slave ownership also spread up the Valley. In the Provincial Enumeration in 1754-55 of Negro Slaves Sixteen Years or Older, a total of 75 were counted in Hampshire County, which then meant all of Western Massachusetts. Scholar Robert Romer notes, however, that numbers for more than half the Valley settlements were lost or never tabulated. Those missing numbers included Deerfield, where he discovered at least 25 slaves were owned. Numbers are not provided for Northampton, either.

Romer was surprised to discover that a significant number of ministers in the Valley owned slaves. In account books, estate papers and Probate court records, he found evidence to list slave-holding religious leaders in at least seventeen communities. Jonathan Edwards, who led Northampton’s Congregation from 1729 to 1750, is among them. In 1731, Edwards went to Newport, Rhode Island to purchase a “Negro Girle named Venus” for eighty pounds. He bought other slaves during his Northampton ministry, owned a slave called Rose when he left for Stockbridge in 1750, and “a negro boy named Titus,” at the time of his death in 1758.

Edwards’ enslavement of others has been most thoroughly researched by scholar Kenneth Minkema. In his paper on “… Edwards’ Defense of Slavery,” he notes “that within Northampton, a small but growing number of elites typically owned one or two slaves— a female for domestic chores and a male for fieldwork—and Edwards was willing to commit a substantial part of his annual salary to establish his membership in this select group.” He mentions that these elite included prominent merchants, politicians, and militia officers, among them John Stoddard, Maj. Ebenezer Pomeroy, and Col. Timothy Wright.

Puritans in Massachusetts regarded themselves as God’s Elect, and so they had no difficulty with slavery, which had the sanction of the Law of the God of Israel. The Calvinist doctrine of predestination easily supported Puritans in a position that Blacks were a people cursed and condemned by God to serve whites. Jonathan Edwards subscribed to this thinking and defended another minister in the Valley criticized by his congregation for, among other things, owning slaves.

Lorenzo Greene’s the Negro in Colonial New England is by cited Douglass Harper for his early (1942) establishment of factual information, including population. The number of blacks in Massachusetts increased ten-fold between 1676 and 1720, from 200 to 2000.The population then doubled from 2,600 in 1735 to 5,235 in 1764, by which time blacks, not all of whom were slaves, had become approximately 2.2 percent of the total Massachusetts population. They were generally concentrated in the industrial and coastal towns, with Boston in 1752 having the highest concentration at 10%.

The black population of colonial Western Massachusetts was slower to grow than the eastern part of the colony, as well as being in smaller numbers, but also shows a pattern of increase. According to William Piersen’s Black Yankees tabulation the Western counties’ black population grew from 74 [under]counted in 1754 to 5,983 in 1790. This also reflected an increasing percentage of Massachusetts total black population, from 3 to 12%. Though Northampton numbers weren’t included in the 1755 Enumeration of Slaves, the fact of Jonathan Edwards’ being an enslaver suggests there were others owned and uncounted in the plantation at that time. That the numbers increased in subsequent years is suggested by the findings reported by Trumbull.

These are the few sentences in James Trumbull’s History of Northampton acknowledging that the settlement practiced slavery. In his summary of the 1764 King’s Census results, Trumbull writes:

“In addition [to a population of 1,274 whites] there were ten negroes, five males and five females. Apparently they were nearly all slaves, and were distributed in the following families: Mrs. Prudence Stoddard, widow of Col. John, one female; Lieut. Caleb Strong, one male; Joseph and Jonathan Clapp, one each; Joseph Hunt one of each sex. There was one negro at Moses Kingsley’s, not a slave, another at Zadoc Danks, and Bathsheba Hull was then living near South Street bridge. [Author’s note: the arithmetic is dodgy.] “

Little is known about these few identified Africans. A Trumbull footnote later in his history adds, “…before the Revolution, Midah, a negro employed in the tannery of Caleb Strong Sr., was the principal fiddler in town.” In another passage, he describes Bathsheba Hull in 1765 as “a negress, widow of Amos Hull, and occupied a small house on the Island near South Street Bridge, formed by the Mill Trench.” The town claimed the land had been illegally squatted on and wished to evict her. Two years later, they had apparently bought her out and paid to move her to lower Pleasant Street.

Bathsheba Hull is also mentioned in Mr. and Mrs. Prince, the acclaimed history by Gretchen Holbrook Gerzina. Abijah Prince, recently freed in Northfield, lived in Northampton from 1752 to 1754. He stayed with Amos and Bathsheba Hull, suggesting a circle of acquaintance among free Black former slaves in the Valley, some of whom owned property. Gerzina writes that Bijah (short for Abijah) worked for the hatter and church deacon Ebenezer Hunt, and that Amos, a freed former slave, was the servant of Hunt’s brother. As the Hulls were starting a family, they rented a farm. There is a gap in the story, with no explanation of how or when Amos died, or how the widow wound up living by the South Street bridge, or where or how many children they had. Later in the time Gerzina finds Bathsheba and children living in Stockbridge.

Gerzina observes that while slavery in the North may have been less violent than that of the South, it was still slavery. Children and parents were sold away from each other, and freedom only came when a white person granted it. They, like their southern counterparts, ran away in large numbers, worked in the fields and houses of their owners, and were hired out without receiving any pay. Unlike southern slaves, however, they traveled between towns easily, could marry, learned to read, and had to attend church. In eighteenth century rural New England, the enslaved carried arms for hunting, military service, and protection. Still, Gerzina found, there were also suicides.

People had their names taken from them when they were enslaved. The Africans were given names by their new owners, often biblical or mythological, and rarely with a surname except as an indication of race or status. This stripping of personal identity continued beyond their deaths as historians have had to struggle to find the record of their lives. Abijah Negro is listed on the Northfield poll tax, and Abijah Prince is also in records as, after his manumission, Abijah Freeman.

In addition to those in Northampton identified by Trumbull and Minkema, Robert Romer’s research added another seven names, for a total of at least fifteen slaveholders in Northampton. We do not know yet how many more there were or who the enslaved people were.

We also don’t know how those enslaved made the transition to being free women and men. In 1780, when the Massachusetts Constitution went into effect, slavery was still legal. Over the next several years, Freedom suits brought to court by those enslaved established that slavery wasn’t compatible with the new Constitution that declared “all men are born free and equal.” By the first federal census, which was in 1790, no one in Massachusetts was willing to go on record as still owning slaves. One assumes they all had either been sold out of state, freed to set up their own lives, or continued as hired-for-wages workers. This change in status is a whole other story. The data for Northampton is missing, however, so we can only guess that there were some – as the census put it — “all other [than white] free people” living here.

Historic Northampton is presently engaged in a long-term research project to identify and learn more about the lives of enslaved people in Northampton. Emma Winter Zeig is leading the project and, with interns, is systematically combing through all public and related private records. About thirty five enslaved people have been identified so far. Searches of the slaveholding family papers for any details are underway. Emma reports that the research is most complicated by lack of records. The researchers have been able to establish some surnames, identified familial relationships, and found more documentation of networks of relationship between people of color in Northampton. Some of their favorite finds have been the few sources that shed light on the daily lives of enslaved people_what Amos Hull was asked at catechism, for example. The project’s long term goal is to link with similar information from other towns to create a region-wide picture.

Two stones , side by side, mark the graves of two black women in the Bridge Street Cemetery in Northampton. They read:

“SYLVA CHURCH b. 1756 d. April 12, 1822 Sacred to the Memory of Sylva Church A Coloured woman, who for many years lived in the family of N. Storrs, died 12 April, 1822, Very few possessed more good qualities than she did. She was for many years a member of Mr. Williams’ Church, and we trust lived agreeable to her profession, and is now inheriting the promises.“

“SARAH GRAY b. 1808 d. 1831 In memory of SARAH GRAY a coloured woman, By those who experienced her faithful services She died Oct. 7, 1831 Aged 23

Northampton author Susan Stinson’s novel Spider in the Tree is a fictional account of Reverend Jonathan Edwards that includes his slaveholding. Susan has given tours of the Bridge Street Cemetery. On one such occasion, she was approached by Frank Carbin, whose sister came on the tour one year, and pointed Susan to a reference that confirmed that Sylva Church was enslaved in the household of Jonathan Edwards’ daughter and later granddaughter.

“There was a slave woman, “Lil”, as she was called, or Sylvia Church (her true name), who was too important a character in the household of Major Dwight and his widow, not to deserve at least a brief remembrance. She was bought on Long Island, when but 9 years old, and lived to advanced years, dying April 12, 1822, being, as is supposed, at that time, 66 years old. The last 15 years of her life she spent with Mrs. Storrs, dau. of Major Dwight. She was pious, faithful, industrious and economical. She had ‘all the pride of the family’ in her heart. She ruled the children of the house and indeed the whole street. She was in fact a strong-minded woman and a ‘character’ in the most striking sense of the word. Says John Tappan, Esq.,..”In addition to the fascination of the parlor, there was the faithful African in the kitchen, by the name of ‘Lilly,’ who ever welcomed me and was not one whit behind her mistress in fascinating my young heart.” At more than 40 years, she was hopefully made a member of Christ’s kingdom, when she first learned to read her Bible, which before had no attractions to her. ..” from The History of the Descendants of John Dwight of Dedham, Mass, by Benjamin W. Dwight, pages 130-140, John Trow & Sons, Printers & Bookbinders, NY, 1874.

Bob Drinkwater would point out that these gravestones are white markers for people of color. In his book about searching for the gravestones of African Americans in Western Massachusetts, In Memory of Susan Freedom, he states that many-perhaps most- early Massachusetts residents of color now lie forgotten in unmarked graves on the periphery of common burying grounds and municipal cemeteries. If they were marked at all, it was often with field stones.

Drinkwater believes these two black women’s graves were once segregated at the edge of the cemetery, before white burials expanded around them. Standing side by side he posits that the younger Sarah Gray served in the same household. Elsewhere in the Bridge Street cemetery, he noted at least a few other gravestones for African Americans, buried several decades later, among their white neighbors. One is for Samuel Blakeman who died in 1879. Another is for Mattie “a Negro” who died in 1862. Far fewer graves are evident than the many people we are coming to know once lived and worked in Northampton. Just as the lives of Northampton’s early black residents were often left out of the written record, so too their deaths.

Sources:

__Massachusetts: a Concise History by Richard D. Brown and Jack Tager. The revised edition was published in 2000 by the University of Massachusetts Press, Amherst.

__Trumbull, James Russell. History of Northampton Massachusetts: From its Settlement in 1654. Volume I. 1898, Volume II. 1902. Northampton.

__Romer, Robert H. Slavery in the Connecticut Valley of Massachusetts. Levellers Press, Florence MA. 2009.

__Warren, Wendy. New England Bound: Slavery and Colonization in Early America. W.W. Norton & Company, New York, London. 2016

__Hardesty, Jared Ross. Black Lives, Native Lands, White Worlds: A History of Slavery in New England. University of Massachusetts Press, Amherst and Boston MA. 2019.

__Carvalho III, Joseph. Black Families in Hampden County, Massachusetts 1650-1865. Revised second edition, 2010. Accessed on academia.edu Oct. 26, 2020.

__Minkema, Kenneth P. ”Jonathan Edward’s Defense of Slavery.” Massachusetts Historical Review, Vol. 4, Race & Slavery (2002), pp.23-59. Massachusetts Historical Society. Courtesy of Historic Northampton.

__Minkema, Kenneth P. “Jonathan Edwards on Slavery and the Slave Trade.” The William and Mary Quarterly, Vol. 54. No. 4 (Oct., 1997), pp. 823-834. Omohondro Institute of Early American History. Courtesy of Historic Northampton

__Harper, Douglass. “Slavery in Massachusetts.” Slavery in the North. Retrieved 2020, Aug 6. http://slavenorth.com/massachusetts.htm.

__Greene, Lorenzo J. The Negro in Colonial New England 1620-1776. Atheneum , New York. edition 1968 of original 1942.

__Piersen, William D. Black Yankees: The Development of an Afro-American Subculture in Eighteenth-Century New England. University of Massachusetts press. Amherst. 1988.

__Gerzina, Gretchen Holbrook. Mr. and Mrs. Prince: How an Extraordinary Eighteenth-Century Family Moved Out of Slavery and Into Legend. HarperCollins Publishers, New York,NY. 2008. My favorite history book, not only local and very readable but illuminating the lives of enslaved blacks and how history is written.

__Sweet, John Wood. Bodies Politic: Negotiating Race in the American North, 1730-1830. University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia PA. 2003.

__Sharpe, Elizabeth and Zeig, Emma Winter. Historic Northampton. Email correspondence Aug-Sep, 2020.

__Bureau of the Census. Bicentennial Edition: Historical Statistics of the United States, Colonial Times to 1970. Part 2, Chapter Z.Series Z 1-19 Estimated Population of American Colonies: 1610-1780. Colonial and Pre-Federal Statistics.

__Stinson, Susan. Spider in a Tree: a novel of the First Great Awakening. Small Beer Press Easthampton MA. 2013.

__Stinson, Susan. Email correspondence Sep. 2020.

__Drinkwater, Bob. In Memory of Susan Freedom: Searching for Gravestones of African Americans in Western Massachusetts. Levellers Press. Amherst MA. 2020.

Ending the Campaign of Terror

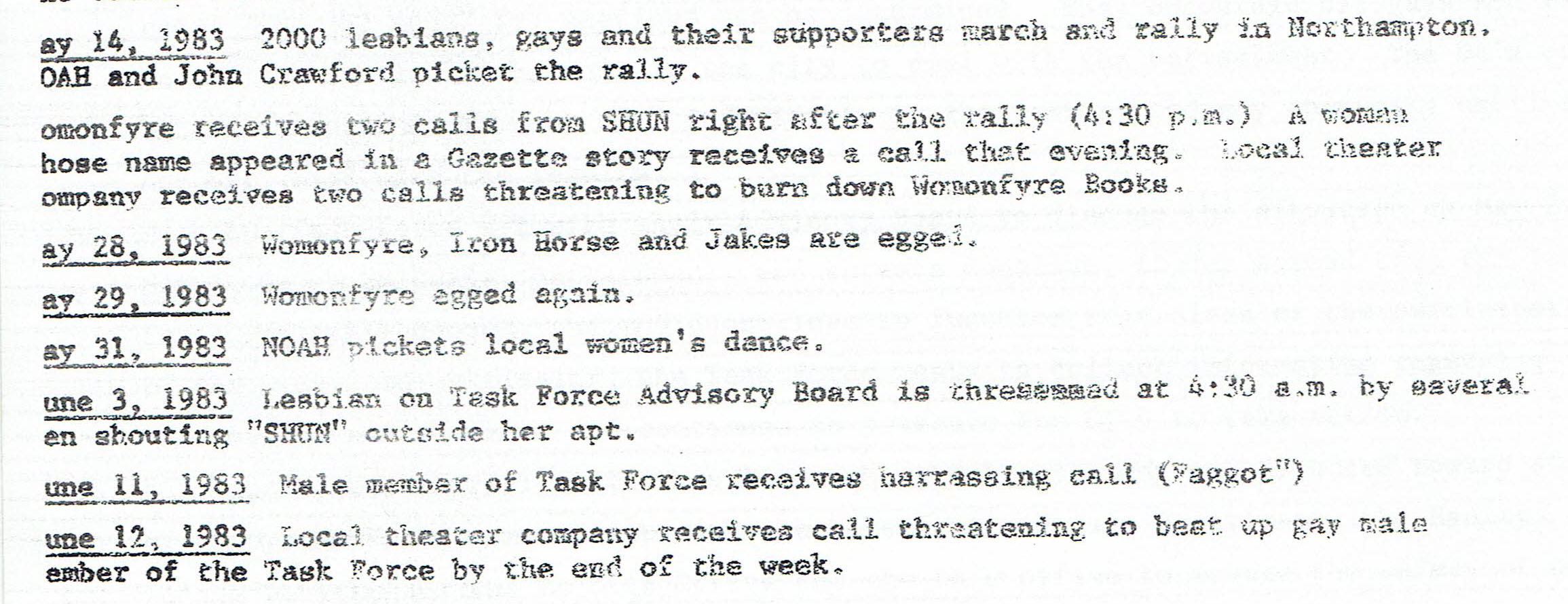

Unless you count the teenage boys calling names or speeding through on their bikes with signs bearing slurs, whoever was making threats of violence in Northampton under the name of SHUN (Stop Homosexual Unity Now) did not have the courage to make themselves known at the second March for Gay and Lesbian Rights in Northampton, MA on May 14, 1983. But the campaign of harassment continued with more phone calls that very afternoon.

In the month following the March, ”Harassment Chronology.” Lesbian and Gay Task Force Newsletter. Northampton MA. June 1983. Courtesy of Bambi Gauthier.

In the month following the March, ”Harassment Chronology.” Lesbian and Gay Task Force Newsletter. Northampton MA. June 1983. Courtesy of Bambi Gauthier.

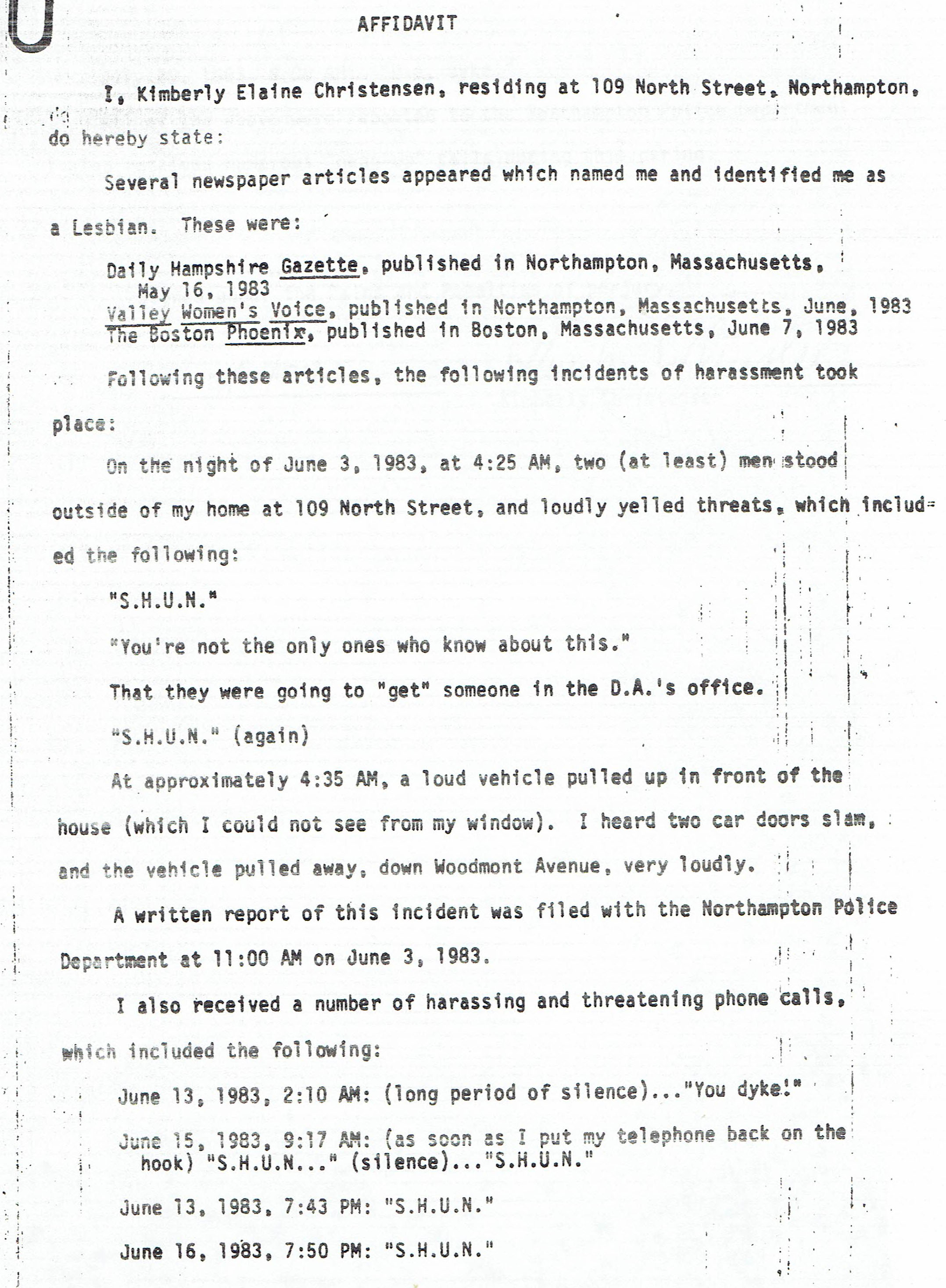

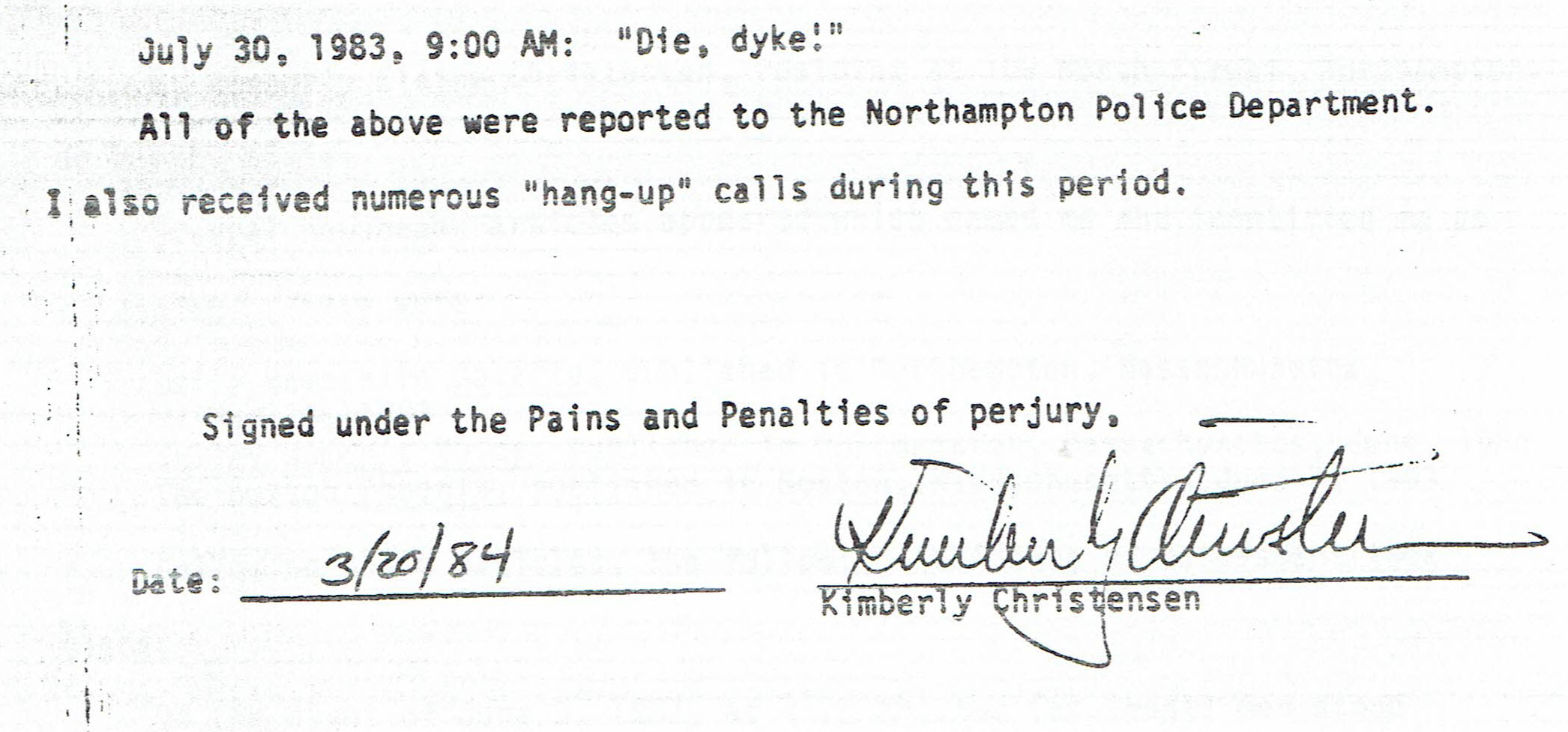

Over the next few weeks, eggs were sporadically thrown by unknown persons at Womonfyre Bookstore at 22 Center Street, the most publically visible sponsor of Lesbian events. Kim Christensen, the March’s spokesperson, who had made her phone number public in order to answer City official and press queries, received not only phone calls but 4:30 a.m. visits from males who stood shouting outside her home.

Affidavit from Kim Christensen harassment experienced by her Jun-Jul 1983.

Affidavit from Kim Christensen harassment experienced by her Jun-Jul 1983.

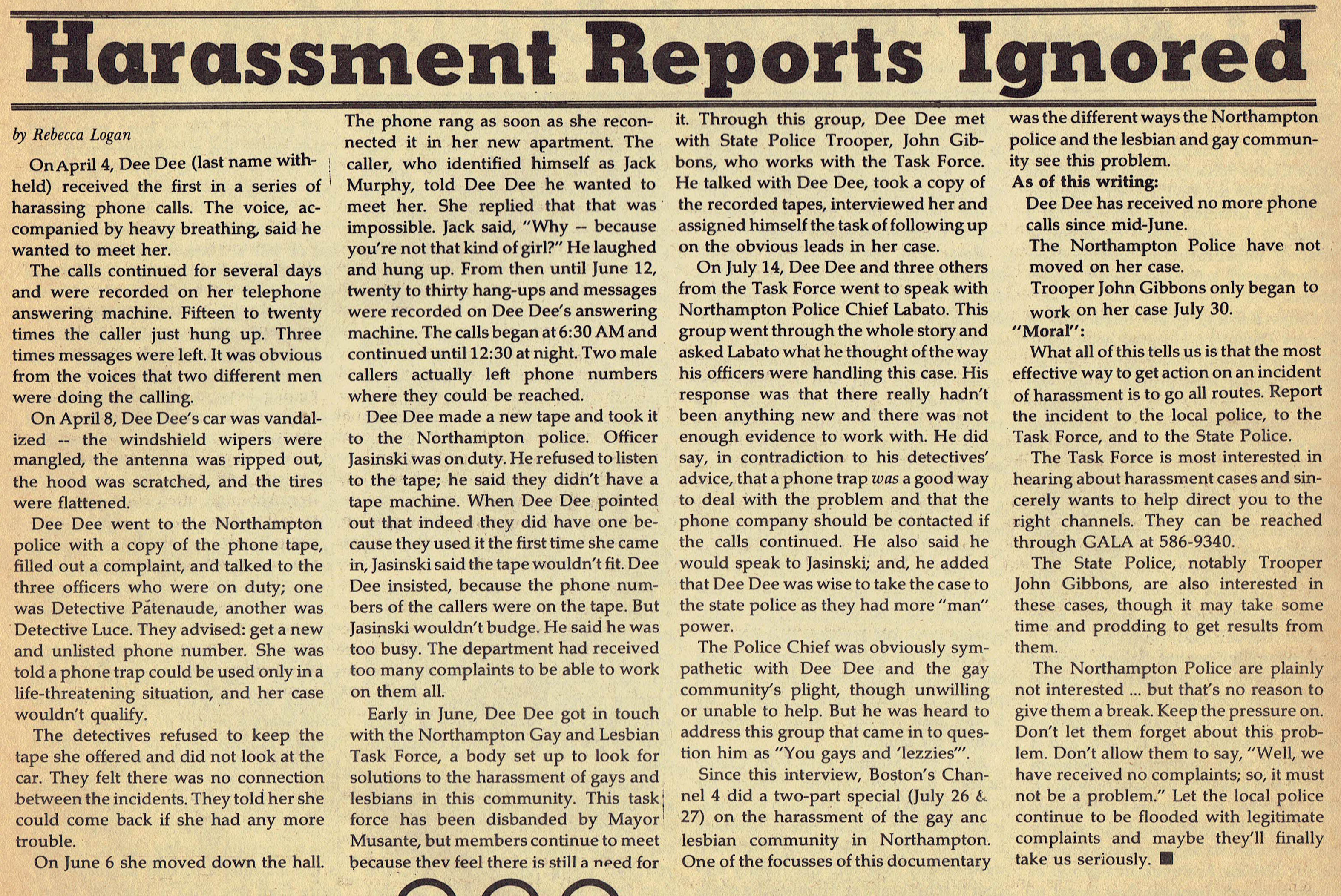

One lesbian began receiving as many as thirty phone calls a day. When this woman went to City police, on-duty officers refused to take her complaint or listen to the message machine tape and misinformed her about what could be done. Only after contacting the Northampton Lesbian/Gay Task Force was she able to make her complaint to the police, with the support of Task Force members. It was reported in the Valley Women’s Voice that while Northampton Police Chief Labato appeared sympathetic, he referred to her and accompanying Task Force members as “you gays and lezzies.”

“Harassment Reports Ignored.” Valley Women’s Voice. Northampton MA. Sep. 1983.

“Harassment Reports Ignored.” Valley Women’s Voice. Northampton MA. Sep. 1983.

The Task Force strongly disagreed with Mayor Musante’s decision to disband the group because he thought that their work was done. The group continued to work to stop the violence after being disbanded by the Mayor. While the Mayor, his assistant and the Northampton Police representative withdrew, the three Lesbians and three gay men, and the Assistant DA Dave Angier continued to meet. In response to the ongoing threats Angier got the DA’s office to assign State Police Trooper John Gibbons to join him in working with the group. The Task Force encouraged the communities to report any incidents to the DA, Police and Task Force. While the Lesbian and Gay Task Force members names were kept confidential, under pressure, when one man allowed his name to be public he also became a target. Threats to beat “faggots” began.

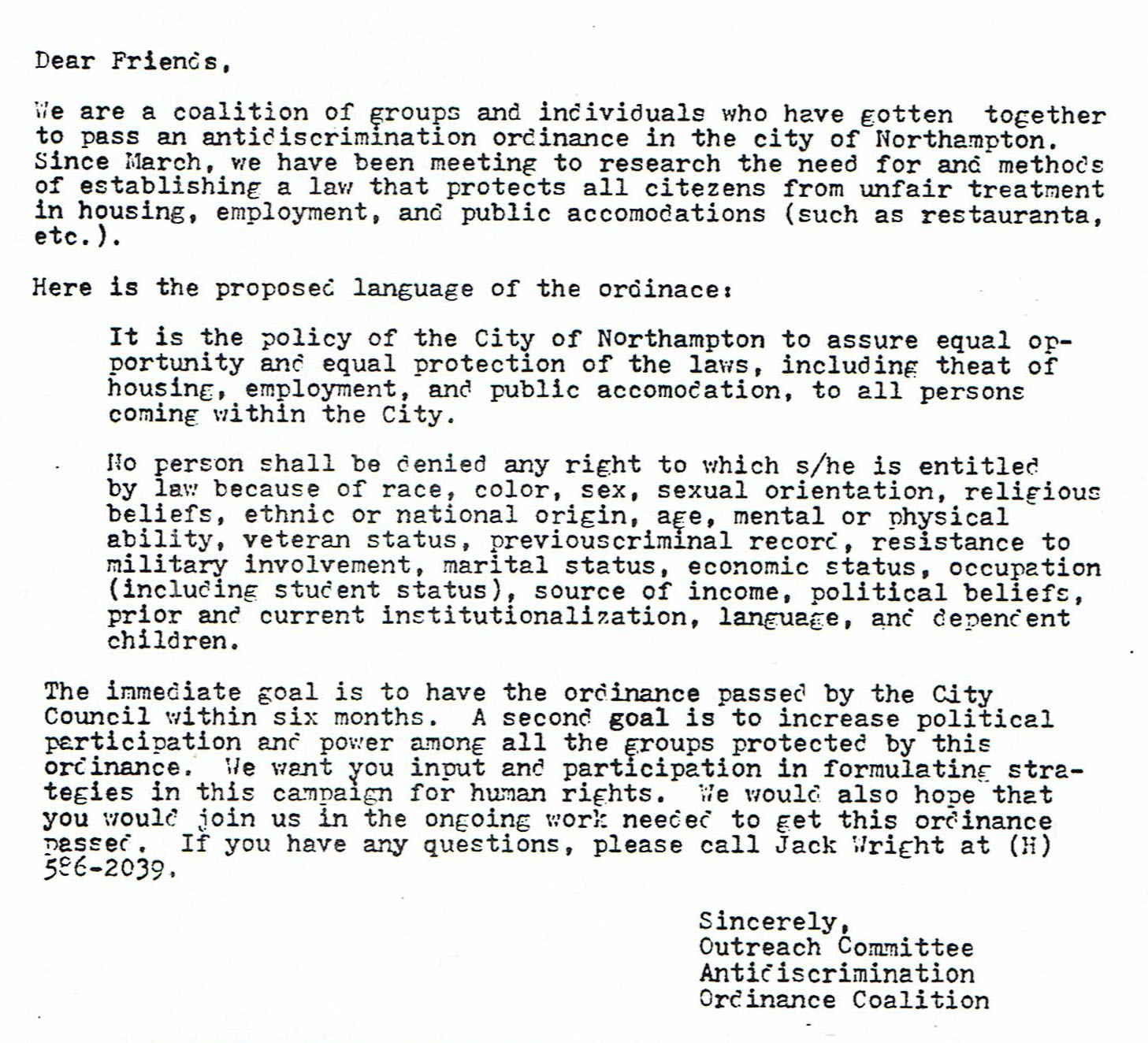

Other people in the community were working on a City anti-discrimination ordinance. In July, after four months work, N’CAN, the Northampton Citizens Action Network, circulated a draft ordinance and asked for help to get it passed in the coming year. That same month, the task of educating the people of Northampton was aided by a series of articles on the community written by Maureen Fitzgerald for the Daily Hampshire Gazette. At the same time, Boston’s Channel 4 aired a two-part special on the harassment in Northampton.

Outreach Committee, Antidiscrimination Ordinance Coalition. Letter. PVPGA Gayzette. July 1983. Courtesy of Bambi Gauthier.

Outreach Committee, Antidiscrimination Ordinance Coalition. Letter. PVPGA Gayzette. July 1983. Courtesy of Bambi Gauthier.

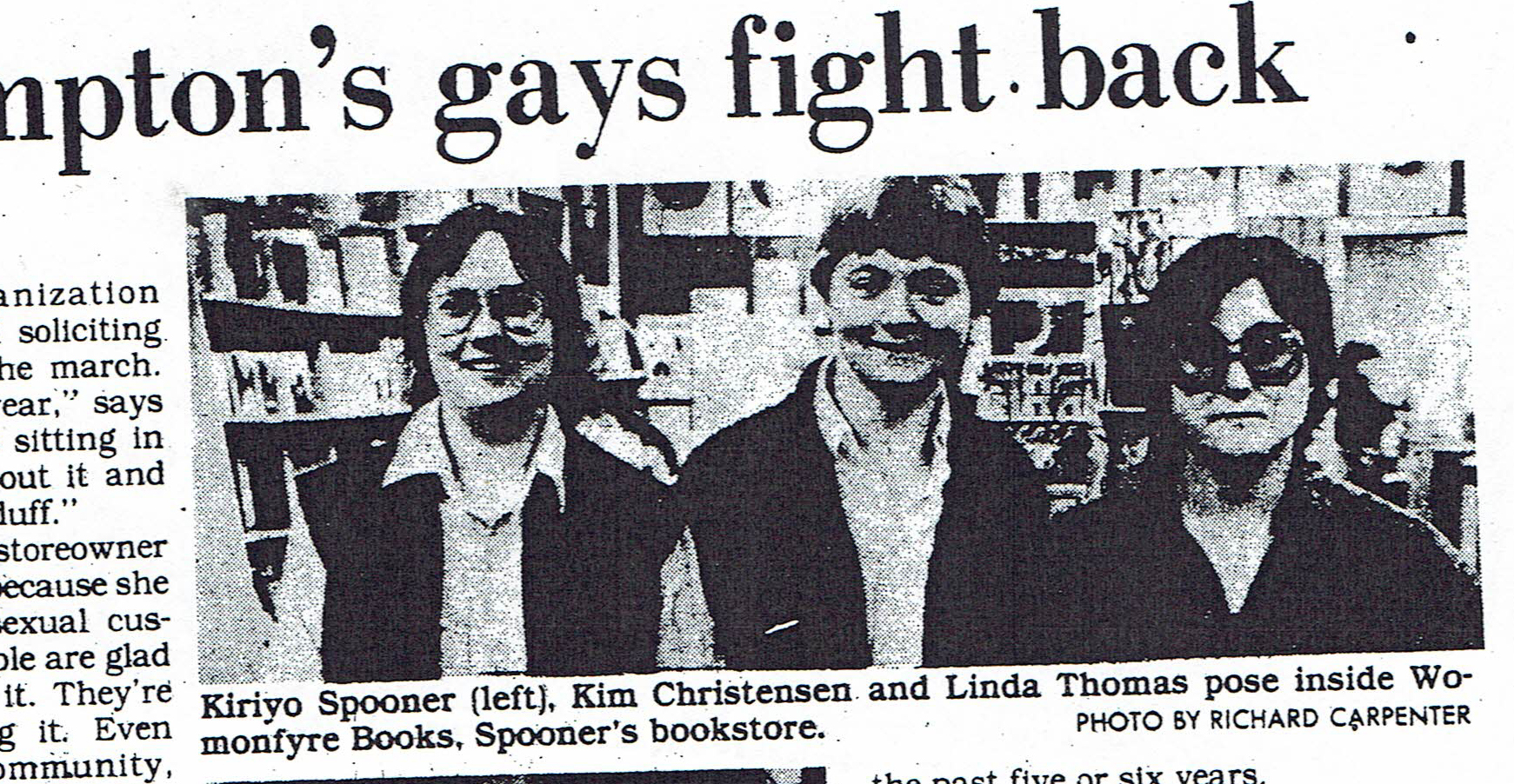

All of this publicity seemed to spur the numerous anonymous males, whose telephoned threats were being taped, into overdrive. As harassment increased, Lesbians working with the DA’s office finally agreed to help set up a phone trap. The co-owners of Womonfyre Books and Kim Christensen worked with ADA Angier and the city police to put it in place. Lesbian events were deliberately advertised with a home phone number. One of the women stayed home after the advertisement appeared to monitor the phone calls and tape them with a machine furnished by the DA’s office. As threatening calls came in, the time was to be noted so that the phone company could then trace specific calls to the phone from which they were made.

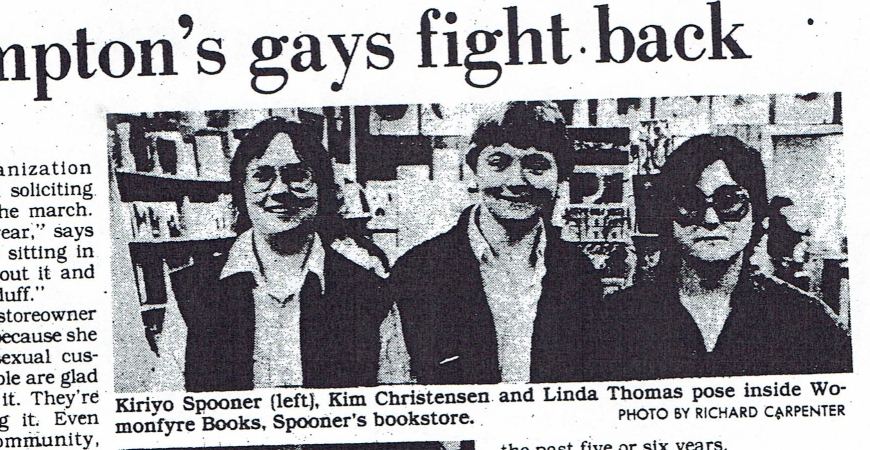

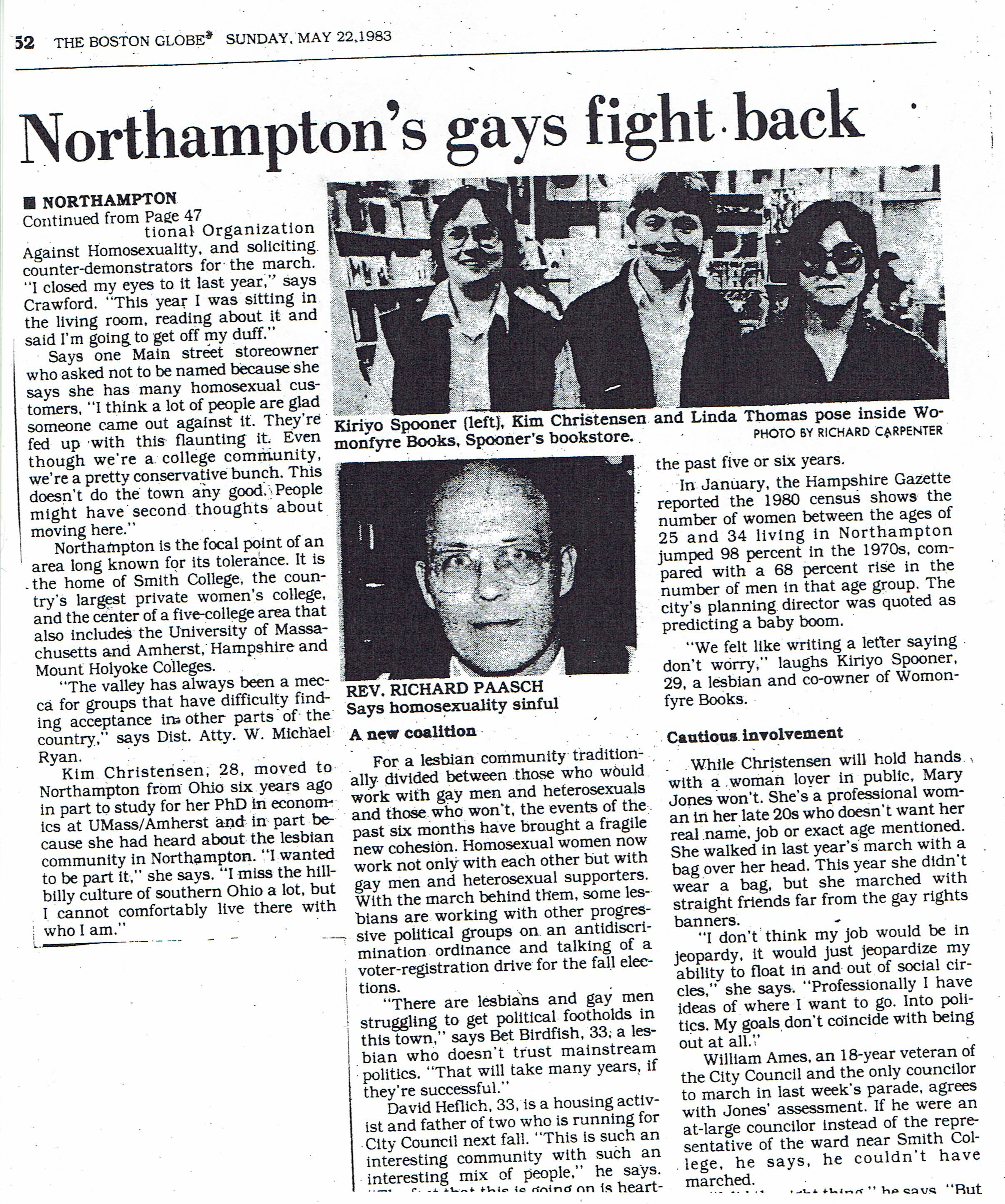

Two of the three women who were key to trapping one of the harassers, Kiriyo and Kim. Bookstore co-owner Jil Krolik isn’t pictured. “Northampton’s Gays Fight Back.” Boston Globe. Boston MA. May 22, 1983.

Two of the three women who were key to trapping one of the harassers, Kiriyo and Kim. Bookstore co-owner Jil Krolik isn’t pictured. “Northampton’s Gays Fight Back.” Boston Globe. Boston MA. May 22, 1983.

“Interestingly,” Kim Christensen recalls, “as soon as the trap was to go into effect, the calls temporarily stopped. Sometimes it was uncanny. E.g., we’d be planning to turn on the phone trap at 9:00 AM and I’d get a call at 8:00, 8:15, 8:30 and 8:57, and then they would stop.” For weeks, the procedure was repeated with the same results. Kim adds, “Finally the ADA decided to put on the trap without notifying the police department beforehand, and boom! a member of SHUN was trapped on the very first attempt. It was extremely suspicious.”

On Saturday, July 30, while the phone trap was in place, thirty-five calls were made by boys and three by an adult male who identified himself as belonging to SHUN. Suspicious events didn’t end there, according to Kim, but continued with difficulties with the local phone company. While the originating phone number could have been identified immediately, the Northampton office refused to give it to the authorities involved. Five days later investigators from the DA’s office, armed with a search warrant, raided the Northampton phone company business office looking for the number, without success. Eventually it had to be obtained from the phone company’s Boston headquarters.

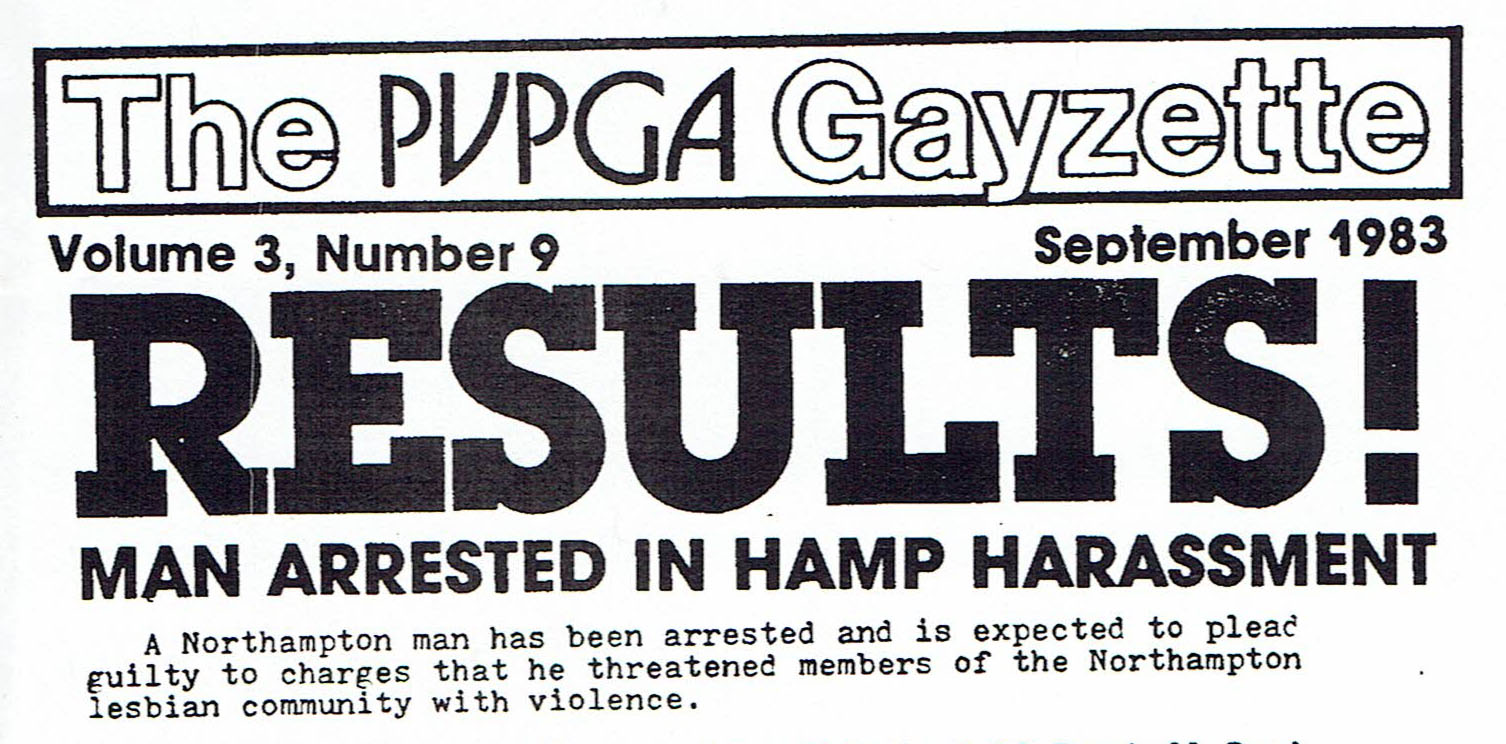

Armed with this information, on Aug. 5 State Police went to the Northampton address identified. They questioned a 23 year-old local male living there. One of his relatives was a former Northampton policeman. After initially denying the charges, the suspect confessed on tape to the State Police that he had made the three July 30 phone calls and he was arrested.

The next day he was formally charged with repeatedly telephoning Jil Krolik for the purpose of harassing and annoying her, and for threatening bodily harm to Kim Christensen and Kiriyo Spooner. Additionally, District Attorney Ryan charged that the threatened reprisals were violations of the women’s civil rights; the rights of free speech and assembly, free association, and privacy.

When the accused agreed to submit to a sufficiency of evidence that indicated his guilt, a sentencing hearing before a judge was set for Aug. 24. A maximum penalty of two and a half years in jail was possible. Though no other males were arrested, calls from SHUN ceased. [If you really want to know his name, you can look it up. He is still living in the area and I will not credit him.]

Although ordered to stay away from the complainants, the guilty male confronted one woman on the street before the next scheduled court appearance and shouted names at her. At the Aug. 24 sentencing hearing in Hampshire Superior Court, Sherman Boyson later reported in the PVPGA Gayzette, the defendant’s friends hissed at the testifying lesbians and called them “scum.” The tape from July 30 was played. It included this threat: “We promise systematic violence…Beware when you walk home! Beware when you walk the streets and where you live at night!” Boyson called it quite chilling.

The prosecutors then moved to play the taped confession made by the accused. Before that could be done however, the accused’s lawyer stopped the proceedings, changed his client’s plea to “not guilty,” and asked for a trial. Boysen later surmised that the seriousness of the evidence already presented was clearly pointing toward jail time, which the defendant’s lawyer wished to avoid for his client.

Both the prosecutors and the State Police believed that the accused had made many more threats then the three he had admitted to. In preparation for a jury trial, the PVGA Gayzette reported, the District Attorney’s office made plans to send some of the fifty message tapes accumulated to the FBI for voice analysis in order to determine what additional charges would be made.

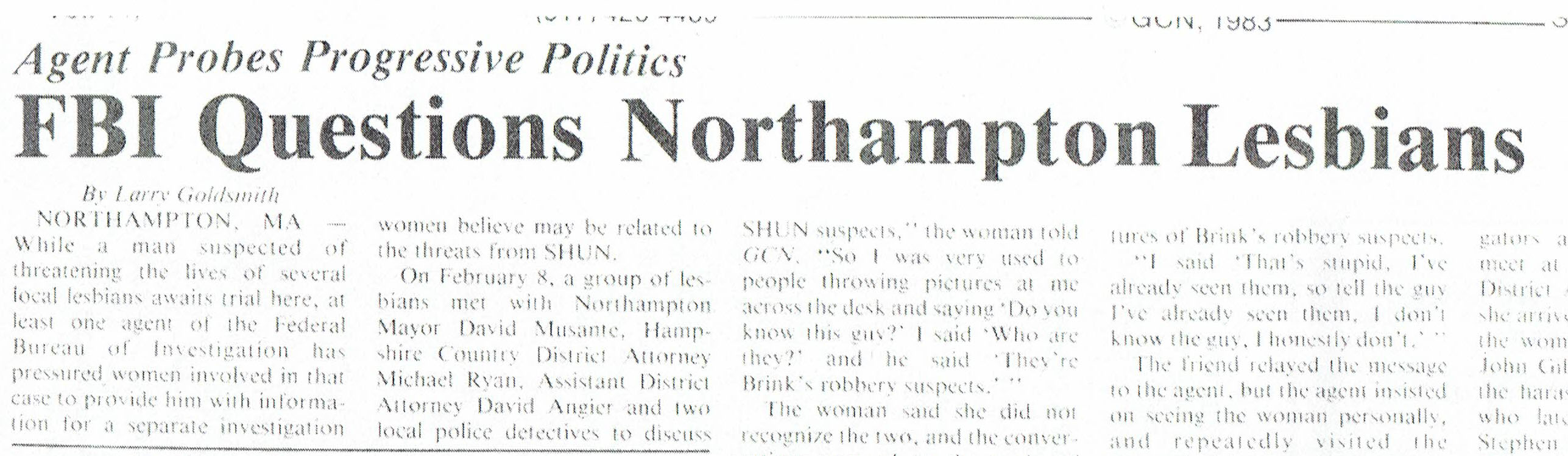

The three complainants continued to aid in preparing the case for trial. One of the woman was alarmed, however, to be asked by the State Trooper and later an FBI agent for information totally unrelated to the case. She was asked to try to identify people in a photos she later learned were suspected members of the Weather Underground. Kim Christensen remembers that the telephone message tapes that would hopefully be analyzed by the FBI were sitting in the room at the time of this interview, and it was made very clear to her by the Agent that cooperation was a two way street.

“FBI Questions Northampton Lesbians: Agent Probes Progressive Politics.” Gay Community News. Boston MA. Sep. 24, 1983. Courtesy of Bambi Gauthier.

“FBI Questions Northampton Lesbians: Agent Probes Progressive Politics.” Gay Community News. Boston MA. Sep. 24, 1983. Courtesy of Bambi Gauthier.

The FBI Agent went on to ask about the size and composition of the Northampton lesbian and gay community, its support for Sandinistas, belief in blowing up buildings, and any coalitions with leftist groups. All three of the women interviewed by the FBI felt pressured to cooperate in this fishing expedition. Kim immediately recognized what was occurring and refused to cooperate. The women sent word out to the community of the FBI’s intrusive presence. No voice analysis was ever done by the FBI to help the court case and the proffered message tapes disappeared. If copies had not been made and kept by the women complainants, there would have been no recorded evidence to present at a trial.

Before a jury could be convened, the confessed harasser changed his mind once again and agreed to submit to facts rather than face a trial. A sentencing hearing was once more scheduled, but before it could take place, his attorney got a continuance so his client could undergo psychiatric testing and counseling. Finally, on Oct. 11, 1983, the hearing resumed before Judge Alvertas Morse in Hampshire Superior Court.

The defendant’s attorney argued that counseling and community service was appropriate punishment, that his client had been raised in a “staunchly Roman Catholic family” which believed homosexuality was immoral, which may have contributed to his feelings against the gay community. Judge Morse, however, found the defendant guilty on all charges and sentenced him to one year in prison, three months of which were to be served and the rest suspended while he was on probation for four years. DA Michael Ryan told the Daily Hampshire Gazette it was the first time anyone in the Commonwealth had been imprisoned for violating a person’s civil rights as guaranteed by the 1980 Massachusetts Civil Rights Law.

I find no record that the male convicted expressed any remorse. Interviewed outside the courthouse after sentencing he blamed his “big mouth” for his behavior. He stated he didn’t know what going to jail would prove. Intimating that he was justified in his behavior, he said, “I would like to know what the community thinks about this,…the Northampton natives.”

In November, all of Northampton’s City Council, the Mayor, and half the School Committee would be up for reelection. In a new chapter of political activism, Lesbians and gay men would demonstrate to the City that they would not only march in the streets but would wield the power of their votes.

The PVPGA Gayzette. Northampton MA. Aug. 1983.

The PVPGA Gayzette. Northampton MA. Aug. 1983.

Sources:

__Sege, Irene. “Northampton’s Gays Fight Back.” Boston Globe. Boston MA. May 22, 1983.

__”Harassment Chronology.” Lesbian and Gay Task Force Newsletter. Northampton MA. June 1983.

__”Brief History of the Task Force.” Lesbian and Gay Task Force Newsletter. Northampton MA. June 1983.

__Christensen, Kimberly. Affidavit: Exhibit R. March 20, 1984.

__Outreach Committee, Antidiscrimination Ordinance Coalition. Letter. PVPGA Gayzette. July 1983.

__Logan, Rebecca. “Harassment Reports Ignored.” Valley Women’s Voice. Northampton MA. Sep. 1983.

__Goldsmith, Larry. “FBI Questions Northampton Lesbians: Agent Probes Progressive Politics.” Gay Community News. Boston MA. Sep. 24, 1983.

__Hasbrouck,Amy. “Fallout From the FBI.” Valley Women’s Voice. Northampton MA. Dec. 1983.

__Christensen, Kim. Email correspondence with Kaymarion Raymond Aug 8- Nov. 17, 2004.

__Blomberg, Marcia. ”Arrest made in phone threats to gays.” Springfield Union. Springfield MA. Aug. 6, 1983.

__”Gay Man Runs for Northampton City Council.” The PVPGA Gayzette. Northampton MA. Aug. 1983.

__Boysen, Sherman. “Results! Man Arrested in Hamp Harassment.” The PVPGA Gayzette. Northampton MA. Sep. 1983.

__”gay man runs for northampton city council seat.” Gay Community News. Boston MA. Sep. 3, 1983.

__Thomas, Linda. “Empowerment by Vote.” Valley Women’s Voice. Northampton MA. Sep. 1983.

__Boysen, Sherman. “…Case Still Not Settled.” The PVPGA Gayzette. Northampton MA. Oct. 1983.

__Fitzgerald, Maureen. “Man jailed for threats to lesbians.” Daily Hampshire Gazette. Northampton MA. Oct. 11, 1983.

Marching In Spite of Threats: 1983

In spite of the continuing threats of murder, arson and unspecified violence from those anonymous males calling themselves SHUN (Stop Homosexual Unity Now) the Gay and Lesbian Activists (GALA) organizers of the Northampton March stepped up efforts to ensure that the event happened a second year, 1983. The March was given an official name , for Gay and Lesbian Rights, with snazzier artwork for publicity , and, once again, scheduled for the second Saturday in May. Organizers aimed to bring out at least a thousand supporters. They made efforts to build a broad coalition as well as to protect the marchers.

Flyer for the March. May 14, 1983. Artist Unknown.

Flyer for the March. May 14, 1983. Artist Unknown.

Invitations to participate were sent not only to progressive groups around the state but also to each of the City Councilors. For the first time, endorsers were sought to buy a full-page ad in the Daily Hampshire Gazette. Only three hundred donors were needed to pay for it. When it was published the day before the March, it included the names over 600 individuals and groups. It read, in part: “The harassment, the threats, the violence directed at gays and lesbians appalls and frightens us. But like the intended victims of this campaign of hate, we are not silenced.” For a history of that previous year of threats of violence see the previous blog post “The Backlash to the First March.” https://fromwickedtowedded.com/2020/05/09/the-backlash-to-the-first-march/

Supporting the right of all people to be free from harassment and fear, the endorsers called on everyone (including straight people) to “Come Out for Justice.” Close to 90% of the endorsing organizations were not focused on gay issues. They came from Boston, Connecticut, New Hampshire, and Western Massachusetts as well as more than thirty Northampton groups and businesses .

Daily Hampshire Gazette May 13, 1983. Full page ad (here partially)

Daily Hampshire Gazette May 13, 1983. Full page ad (here partially)

This first “signature ad” in some ways made up for City government’s foot dragging. The day before the second March, Northampton’s Mayor Musante released a statement on civil rights, but neglected to endorse the event. He had also dissolved the Lesbian/Gay Task Force created to address the communities’ concerns about increasing violence and lack of City government and media responsibility. After only two meetings, he was satisfied it had accomplished all that was needed.

Those anonymous male phone callers identifying themselves as SHUN had threatened to disrupt the March. As March endorsers became public, they, too, were targeted with threats. This included New Jewish Agenda, Hampshire County NOW, Northampton Law Collective, Circa Counseling, and Women’s Community Theatre.

Log of phoned threats on GALA phone answering machine for May 9, 1983.

Log of phoned threats on GALA phone answering machine for May 9, 1983.

In the weeks leading up to the action, a Hatfield man announced in the Daily Hampshire Gazette that NOAH, his newly formed group, would counter-demonstrate that day. The scheduled event also received unanticipated attention when local TV station Springfield Channel 22 aired a five part documentary report the week before the March. “The Changing Lives of Lesbians and Gay Men in the Pioneer Valley,” by Vivian Sandler , included segments on family, religion, culture, and oppression.

For the first time, GALA put out a call for several dozen people to be trained in non-violent intervention and serve as peacekeepers at the March. Over fifty volunteers responded to keep potential conflicts from getting violent. They would appear at the March and the rally to follow it in turquoise T-shirts. Printed on the back of each T-shirt: “An Army of Lovers Can Not Fail.”

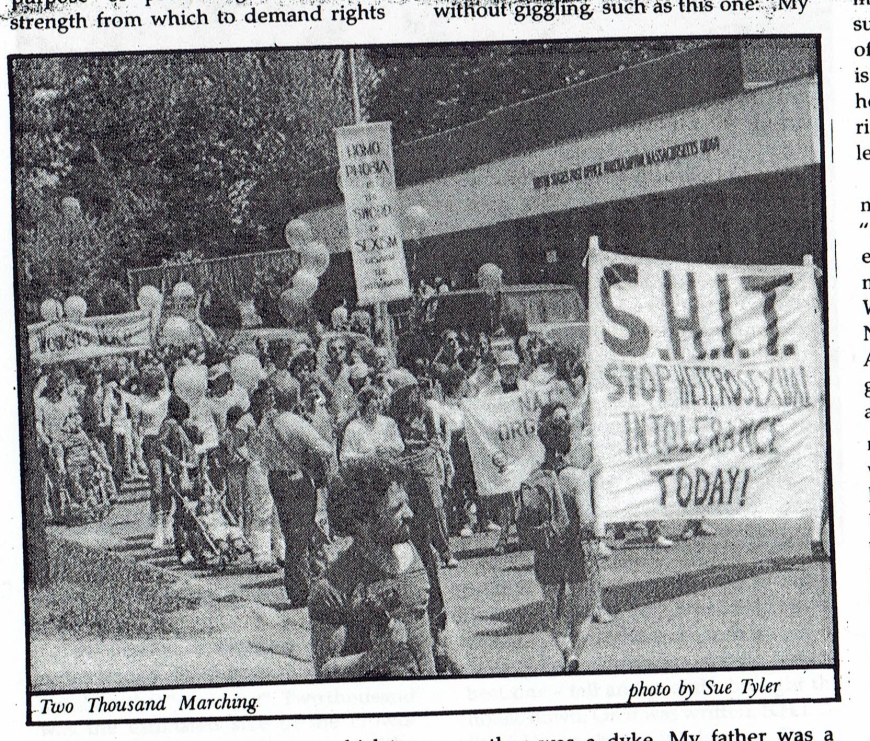

On May 14, 1983, an estimated 2,000 Lesbians , gay men, and supporters turned out to march a circuitous route from Bridge St. School, past City Hall, to Pulaski Park. This was twice the number of marchers anticipated and two to four times that of the previous year. Sherman Boyson, reporting in the Pioneer Valley Peoples Gay Alliance newsletter the Gayzette, found the number of people, with their clever disguises and purple balloons, overwhelming.

The handful of counter demonstrating members of NOAH, “National (Hatfield) Organization Against Homosexuals,” couldn’t believe there were so many ”homosexuals” in the Valley and accused the organizers of bringing them in from out of state. In fact, the great majority were from the Valley, many of whom were “out” at home for the first time.

The singing, chanting, sign-carrying and waving marchers included some people in masks and facepaint (no paper bags this year), babies pushed in strollers, and an occasional gay or lesbian dog. Among the groups with banners were Womonfyre Books, the Valley Women’s Voice, and many others who had been threatened with violence. The hit of the day was the large banner carried by Lydia Nichy and Mary Patierno of Northampton. In a direct response to SHUN’s Stop Homosexual Unity Now, the banner read “Stop Heterosexual Intolerance Today,” or SHIT.

Coverage of the March, Valley Women’s Voice, June 1983. Photo by Sue Tyler.

Coverage of the March, Valley Women’s Voice, June 1983. Photo by Sue Tyler.

Ward 2 Councilor William Ames, one of the few Republicans on the town’s governing body, had, right up to the day of the event, hesitated to join the March even though he had publicly endorsed it. He explained in a DHG story that he had received such angry phone calls in response to the anti-violence statement he had introduced to City Council (which failed to pass) that he feared for his family’s safety. Setting such apprehension aside, however, he joined the passing marchers, becoming the first city official to do so. His colleague, Councilor-At-Large Edward Keefe, became the first official to demonstrate in opposition. The Democrat stood on the sidewalk with NOAH. Other counter demonstrators included about a dozen people from Rev. Paasch ’s Faith Baptist Church in Florence.

Marchers filled Pulaski Park for speeches and entertainment. Gwendolyn Rogers, a Black lesbian mother and activist from Boston, delivered the keynote urging coalition building. Bet Birdfish, the coordinator of the New Alexandria Lesbian Library, spoke about the local harassment and need for community action. Other speakers scheduled included Ron Dion, a gay Springfield lawyer and father, LL Thomas of GALA, and Jerry Fresia, a straight man representing the Northampton Committee on Central America. The Valley Womyn’s Chorus, Vermont folksinger David Gott, and local lesbians Liz Foley and Kore offered entertainment.

Coverage of March Gay Community News, Boston May 29, 1983

Coverage of March Gay Community News, Boston May 29, 1983

The names of endorsing groups were read out at the rally. One precedent-setting list was read by Senator John Olver’s aide Stan Rosenberg, who had called local politicians to poll them about their stance on the March. In addition to several from Amherst and Charlemont, the endorsers he gathered included Olver, Representative William P. Nagle, Northwestern District Attorney Michael Ryan, County Commissioner Robert Garvey, Northampton School Committee members Maria Tymoczki, Susan Peterson, and John Lawlor, and Forbes Library Trustee Russell Carrier.

Although the City Clerk had declined an invitation to set up a voter registration table at the rally, office hours were extended that Saturday so marchers could register. At least thirty Northampton people took advantage of the opportunity and signed up at the City Hall, a few doors away from the Pulaski Park rally.

In spite of threats, the event was enthusiastically joyful. SHUN never made its presence visible. Peacekeepers silently surrounded several groups of heckling teenage boys, who shut up and retreated. One bike-riding boy shouted “Kill Lezbos” as he raced past marchers but other bikers with anti-lgbt signs riding through the rally remained quieter. The celebration continued that night with a dance. Lesbians and gays were now rallied for the actions needed in the coming year to push back the homophobes and end the threats of violence.

Boston Globe coverage of March, May 22, 1983. Rare photo that includes two of the three women who were to bring charges against a male harasser in the coming year, Kiryo Spooner and Kim Christensen.

SOURCES:

__Boysen, Sherman. “Organizing in Northampton: Assessing the Results.” Pioneer Valley Peoples’ Gay Alliance (PVPGA) Gayzette. March 1983.

__ “Northampton Expects a Thousand Marchers.” Pioneer Valley Peoples’ Gay Alliance (PVPGA) Gayzette. May 1983.

__”Gay, Lesbian Rights Focus of May 14 Rally: Counter-protest Possible.” Daily Hampshire Gazette, Northampton MA. May 4, 1983.

__Spooner, Kiriyo. Letter to the [Editor] VWV. Valley Women’s Voice. Northampton MA. May 1983.

__Christensen, Kim. GALA log of harassing phone calls, May 9, 1983.

__Fitzgerald, Maureen. ”Mayor Issues Statement on Civil Rights: Falls Short of Endorsing Gay, Lesbian March.” Daily Hampshire Gazette, Northampton MA. May 10, 1983.

__”We Support Lesbian and Gay Liberation.” Daily Hampshire Gazette, Northampton MA. May 13, 1983. Political advertisement.

__Gay and Lesbian Activists. Northampton MA. Flyer for the March. May 14, 1983. Artist Unknown.

__Northampton Citizens’ Action Network. ”Register to Vote Today!” Flyer circulated at May 14 rally.

__Sege, Irene. Northampton’s gays fight back: Reports of harassment trigger action.” Boston Globe, Boston MA. May 22, 1983.

__Goldsmith, Larry. “Peace and Pride Mark Northampton March.” Gay Community News, Boston MA. May 29, 1983.

__”the March.” Pioneer Valley Peoples’ Gay Alliance (PVPGA) Gayzette. June 1983.

__Logan, Becky. ”A March for Justice.” Valley Women’s Voice. Northampton MA. June 1983 Photos by Sue Tyler.

__Benal, Jolania. The Northampton March: Meeting the Enemy.” Gay Community News, Boston MA. June 25, 1983.