In 1764 Northampton there were at least seven people held in slavery by prominent English colonists. Those enslaved, along with three other people, were listed as being “negroes” in that year’s King George III’s Census, according to historian James Trumbull in his two volume History of Northampton (published 1898 and 1902.) The names of the enslavers, but not the enslaved, were included. It is likely that they were from, or descendants of those from, West Africa, abducted, sold, and exported as merchandise to be resold in the British Colonies.

Three sentences about these ten Black people are the only acknowledgement in Trumbull’s 1300 page History of Northampton that the settlement practiced slavery. Aside from a few additional notes on two of these people, James Trumbull and subsequent town historians omitted mentioning this past as the institution of slavery became unpopular in this region. Robert Romer found this practice of historical erasure common in most of the local area, calling it deliberate amnesia in his history, Slavery in the Connecticut Valley of Massachusetts (2009).. It would be another one hundred years before historians began to rectify this lapse in memory.

The scope of this deliberate amnesia became most readily apparent to me when, this past year, I turned to Massachusetts: a Concise History by Richard D. Brown and Jack Tager. The revised edition was published in 2000 by the University of Massachusetts Press, Amherst. The history includes no mention of slavery until the narrative reaches the 1800s and the developing slavery abolition movement. The false impression given is that slavery was never practiced in Massachusetts. Many, now startling to me, facts about this past have been deliberately left out of historical accounts and, thus, general education.

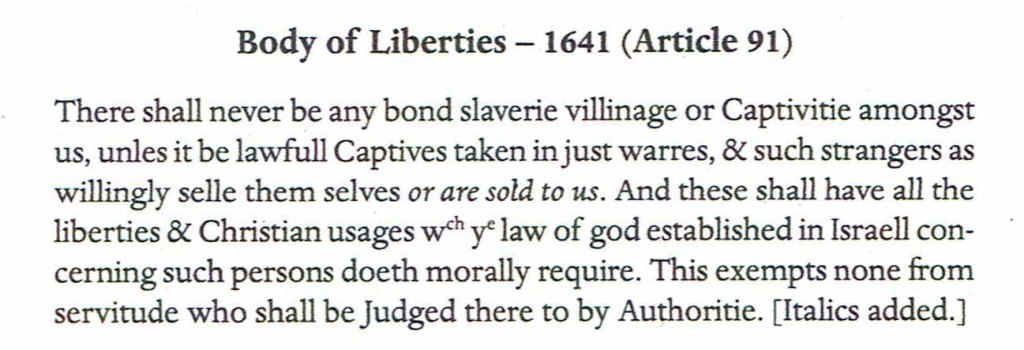

Of the thirteen British colonies, Massachusetts Bay that was the first to explicitly legalize slavery. In 1641, the General Court added an article to the Body of Liberties addressing “bond slaverie.”

Article 91 legally formalized the status of enslaved Africans who, as early as 1638, had begun to be imported and sold in Massachusetts. It also formalized the status of Indigenous people who were captured by the colonists, “taken in just wars,” and as “captives” forced to serve in English households or exported for sale as enslaved. [That is another story for later post.] These actions and the English colonists’ rationale are included in a very recently published history of New England slavery, Jared Ross Hardesty’s Black Lives, Native Lands, White Worlds (2019). Published by the University of Massachusetts Press, Amherst, it begins to fill an egregious gap in their sponsored literature.

During the colonial era, numerous additional laws were passed to control those enslaved in Massachusetts: ensuring that the children of slave women were also enslaved, regulating movement and marriage among slaves, and prohibiting black males from having sex with English women. Massachusetts Bay colony residents increasingly bought slaves, “servants for life.” Some enriched themselves as Boston, an Atlantic port, became one of the largest centers of that trade in the enslaved.

As British colonization spread from the coast up the Connecticut River Valley, so too did slavery. The English first planted themselves in Springfield, founded as a trading post in 1636 by William Pynchon. Though he is not known to have enslaved Africans, Pynchon brought with him an indentured servant Peter Swinck. According to Joseph Carvalho’s history Black Families in Hampden County, Massachusetts (2010) Swinck is the first African American known to have lived in Western Massachusetts. He later was indentured to William’s son and successor John Pynchon. The first record of enslavement in WMass is a note dated 1657 that John had paid a man for “bringing up [the Connecticut River] my negroes.” He is also known to have enslaved at least five Africans between 1680 and 1700. Springfield may have been the first Valley center of trading in the enslaved, with recorded sales made in the 1720s within Springfield and up the river valley.

The earliest mention of enslaved people in Northampton by James Trumbull concerns someone from outside of the settlement, related by him in the segment “Burning of William Clarke’s House:”

” On the night of July 14, 1681, Lt. Clarke’s house caught fire with Clarke, his wife, and grandson within. The tradition is that the door was locked from outside before the fire was set in revenge for some perceived mistreatment inflicted on the arson by Clarke. The residents escaped the log house with effort before an explosion of some combustible blew off the roof tree.”

“Jack, a slave run away from his Wethersfield CT owner was later caught and accused of the arson. He confessed to starting the fire, but claimed it began accidentally when he was inside searching for food by the light of a pine torch. Jack was taken to Boston for trial in the Superior Court. A jury found him guilty and sentenced him to be ‘hanged by the neck till he be dead and then taken down and be burnt to ashes in the fire with Maria, the negro’.”

“Maria was under sentence for burning the houses of [her enslaver and his brother-in-law] in Roxbury. She was burned alive [at the stake]. Both of these negroes were slaves. Why the body of Jack was burned is not known.”

In a footnote, Trumbull adds, “Many slaves were burned alive in New York and New Jersey, and in the southern colonies, but few in Massachusetts.”

Wendy Warren, in her history of slavery and colonization in early America, New England Bound (2016),researched this Sep. 22, 1681 execution by burning, which was the first in New England. From the trial transcript, she was able to add some details to Jack’s story. He testified that he “came from Wethersfield and is Run away from Mr. Samuel Wolcott because he always beates him sometimes with 100 blows so that he hath told his master that he would sometime or other hang himself.” Jack told the court he had been on the run for a week and a half before his capture [somewhere in Hampshire County] by a miller he was trying to rob. A Springfield court sentenced Jack to prison, but he escaped. Thirteen days later he set fire to the house in Northampton.

Earlier, in 1652, because of fires set by “Indians and Negroes,” Massachusetts had passed a law making arson a capital crime, punishable by death. Warren posits that arson was perceived as a particular threat after the conflagrations of the [Pequot] War, and the example of two major uprisings–a servants’ rebellion in Virginia and a slaves’ rebellion on Barbados. Warren wonders if the severity of the form of execution came from the English colonists’ generalized fear of conspiracy and a need to terrify any others who might imitate Maria’s actions. Jack’s body being added to her consuming fire may have been a symbolic linking of their state of enslavement and their crimes.

The challenges of controlling the lives of the enslaved didn’t discourage ownership in Massachusetts. Warren points out that, given large-scale plantation slavery never developed in New England, chattel slavery might be seen as a vanity project of the very wealthy. One such example is merchant John Pynchon of Springfield, who benefited from the increase in West Indies trade. What the wealthy had, the less wealthy also wanted. The population of enslaved Africans in Massachusetts, including the Valley, grew over the next century as increasing numbers of the more well-to-do colonists owned at least one.

From Pynchon’s Springfield, colonial plantations spread up the Connecticut River. Northampton was founded in 1654, Hadley in 1659, Deerfield in 1670, and Northfield in 1673. Over the next century, slave ownership also spread up the Valley. In the Provincial Enumeration in 1754-55 of Negro Slaves Sixteen Years or Older, a total of 75 were counted in Hampshire County, which then meant all of Western Massachusetts. Scholar Robert Romer notes, however, that numbers for more than half the Valley settlements were lost or never tabulated. Those missing numbers included Deerfield, where he discovered at least 25 slaves were owned. Numbers are not provided for Northampton, either.

Romer was surprised to discover that a significant number of ministers in the Valley owned slaves. In account books, estate papers and Probate court records, he found evidence to list slave-holding religious leaders in at least seventeen communities. Jonathan Edwards, who led Northampton’s Congregation from 1729 to 1750, is among them. In 1731, Edwards went to Newport, Rhode Island to purchase a “Negro Girle named Venus” for eighty pounds. He bought other slaves during his Northampton ministry, owned a slave called Rose when he left for Stockbridge in 1750, and “a negro boy named Titus,” at the time of his death in 1758.

Edwards’ enslavement of others has been most thoroughly researched by scholar Kenneth Minkema. In his paper on “… Edwards’ Defense of Slavery,” he notes “that within Northampton, a small but growing number of elites typically owned one or two slaves— a female for domestic chores and a male for fieldwork—and Edwards was willing to commit a substantial part of his annual salary to establish his membership in this select group.” He mentions that these elite included prominent merchants, politicians, and militia officers, among them John Stoddard, Maj. Ebenezer Pomeroy, and Col. Timothy Wright.

Puritans in Massachusetts regarded themselves as God’s Elect, and so they had no difficulty with slavery, which had the sanction of the Law of the God of Israel. The Calvinist doctrine of predestination easily supported Puritans in a position that Blacks were a people cursed and condemned by God to serve whites. Jonathan Edwards subscribed to this thinking and defended another minister in the Valley criticized by his congregation for, among other things, owning slaves.

Lorenzo Greene’s the Negro in Colonial New England is by cited Douglass Harper for his early (1942) establishment of factual information, including population. The number of blacks in Massachusetts increased ten-fold between 1676 and 1720, from 200 to 2000.The population then doubled from 2,600 in 1735 to 5,235 in 1764, by which time blacks, not all of whom were slaves, had become approximately 2.2 percent of the total Massachusetts population. They were generally concentrated in the industrial and coastal towns, with Boston in 1752 having the highest concentration at 10%.

The black population of colonial Western Massachusetts was slower to grow than the eastern part of the colony, as well as being in smaller numbers, but also shows a pattern of increase. According to William Piersen’s Black Yankees tabulation the Western counties’ black population grew from 74 [under]counted in 1754 to 5,983 in 1790. This also reflected an increasing percentage of Massachusetts total black population, from 3 to 12%. Though Northampton numbers weren’t included in the 1755 Enumeration of Slaves, the fact of Jonathan Edwards’ being an enslaver suggests there were others owned and uncounted in the plantation at that time. That the numbers increased in subsequent years is suggested by the findings reported by Trumbull.

These are the few sentences in James Trumbull’s History of Northampton acknowledging that the settlement practiced slavery. In his summary of the 1764 King’s Census results, Trumbull writes:

“In addition [to a population of 1,274 whites] there were ten negroes, five males and five females. Apparently they were nearly all slaves, and were distributed in the following families: Mrs. Prudence Stoddard, widow of Col. John, one female; Lieut. Caleb Strong, one male; Joseph and Jonathan Clapp, one each; Joseph Hunt one of each sex. There was one negro at Moses Kingsley’s, not a slave, another at Zadoc Danks, and Bathsheba Hull was then living near South Street bridge. [Author’s note: the arithmetic is dodgy.] “

Little is known about these few identified Africans. A Trumbull footnote later in his history adds, “…before the Revolution, Midah, a negro employed in the tannery of Caleb Strong Sr., was the principal fiddler in town.” In another passage, he describes Bathsheba Hull in 1765 as “a negress, widow of Amos Hull, and occupied a small house on the Island near South Street Bridge, formed by the Mill Trench.” The town claimed the land had been illegally squatted on and wished to evict her. Two years later, they had apparently bought her out and paid to move her to lower Pleasant Street.

Bathsheba Hull is also mentioned in Mr. and Mrs. Prince, the acclaimed history by Gretchen Holbrook Gerzina. Abijah Prince, recently freed in Northfield, lived in Northampton from 1752 to 1754. He stayed with Amos and Bathsheba Hull, suggesting a circle of acquaintance among free Black former slaves in the Valley, some of whom owned property. Gerzina writes that Bijah (short for Abijah) worked for the hatter and church deacon Ebenezer Hunt, and that Amos, a freed former slave, was the servant of Hunt’s brother. As the Hulls were starting a family, they rented a farm. There is a gap in the story, with no explanation of how or when Amos died, or how the widow wound up living by the South Street bridge, or where or how many children they had. Later in the time Gerzina finds Bathsheba and children living in Stockbridge.

Gerzina observes that while slavery in the North may have been less violent than that of the South, it was still slavery. Children and parents were sold away from each other, and freedom only came when a white person granted it. They, like their southern counterparts, ran away in large numbers, worked in the fields and houses of their owners, and were hired out without receiving any pay. Unlike southern slaves, however, they traveled between towns easily, could marry, learned to read, and had to attend church. In eighteenth century rural New England, the enslaved carried arms for hunting, military service, and protection. Still, Gerzina found, there were also suicides.

People had their names taken from them when they were enslaved. The Africans were given names by their new owners, often biblical or mythological, and rarely with a surname except as an indication of race or status. This stripping of personal identity continued beyond their deaths as historians have had to struggle to find the record of their lives. Abijah Negro is listed on the Northfield poll tax, and Abijah Prince is also in records as, after his manumission, Abijah Freeman.

In addition to those in Northampton identified by Trumbull and Minkema, Robert Romer’s research added another seven names, for a total of at least fifteen slaveholders in Northampton. We do not know yet how many more there were or who the enslaved people were.

We also don’t know how those enslaved made the transition to being free women and men. In 1780, when the Massachusetts Constitution went into effect, slavery was still legal. Over the next several years, Freedom suits brought to court by those enslaved established that slavery wasn’t compatible with the new Constitution that declared “all men are born free and equal.” By the first federal census, which was in 1790, no one in Massachusetts was willing to go on record as still owning slaves. One assumes they all had either been sold out of state, freed to set up their own lives, or continued as hired-for-wages workers. This change in status is a whole other story. The data for Northampton is missing, however, so we can only guess that there were some – as the census put it — “all other [than white] free people” living here.

Historic Northampton is presently engaged in a long-term research project to identify and learn more about the lives of enslaved people in Northampton. Emma Winter Zeig is leading the project and, with interns, is systematically combing through all public and related private records. About thirty five enslaved people have been identified so far. Searches of the slaveholding family papers for any details are underway. Emma reports that the research is most complicated by lack of records. The researchers have been able to establish some surnames, identified familial relationships, and found more documentation of networks of relationship between people of color in Northampton. Some of their favorite finds have been the few sources that shed light on the daily lives of enslaved people_what Amos Hull was asked at catechism, for example. The project’s long term goal is to link with similar information from other towns to create a region-wide picture.

Two stones , side by side, mark the graves of two black women in the Bridge Street Cemetery in Northampton. They read:

“SYLVA CHURCH b. 1756 d. April 12, 1822 Sacred to the Memory of Sylva Church A Coloured woman, who for many years lived in the family of N. Storrs, died 12 April, 1822, Very few possessed more good qualities than she did. She was for many years a member of Mr. Williams’ Church, and we trust lived agreeable to her profession, and is now inheriting the promises.“

“SARAH GRAY b. 1808 d. 1831 In memory of SARAH GRAY a coloured woman, By those who experienced her faithful services She died Oct. 7, 1831 Aged 23

Northampton author Susan Stinson’s novel Spider in the Tree is a fictional account of Reverend Jonathan Edwards that includes his slaveholding. Susan has given tours of the Bridge Street Cemetery. On one such occasion, she was approached by Frank Carbin, whose sister came on the tour one year, and pointed Susan to a reference that confirmed that Sylva Church was enslaved in the household of Jonathan Edwards’ daughter and later granddaughter.

“There was a slave woman, “Lil”, as she was called, or Sylvia Church (her true name), who was too important a character in the household of Major Dwight and his widow, not to deserve at least a brief remembrance. She was bought on Long Island, when but 9 years old, and lived to advanced years, dying April 12, 1822, being, as is supposed, at that time, 66 years old. The last 15 years of her life she spent with Mrs. Storrs, dau. of Major Dwight. She was pious, faithful, industrious and economical. She had ‘all the pride of the family’ in her heart. She ruled the children of the house and indeed the whole street. She was in fact a strong-minded woman and a ‘character’ in the most striking sense of the word. Says John Tappan, Esq.,..”In addition to the fascination of the parlor, there was the faithful African in the kitchen, by the name of ‘Lilly,’ who ever welcomed me and was not one whit behind her mistress in fascinating my young heart.” At more than 40 years, she was hopefully made a member of Christ’s kingdom, when she first learned to read her Bible, which before had no attractions to her. ..” from The History of the Descendants of John Dwight of Dedham, Mass, by Benjamin W. Dwight, pages 130-140, John Trow & Sons, Printers & Bookbinders, NY, 1874.

Bob Drinkwater would point out that these gravestones are white markers for people of color. In his book about searching for the gravestones of African Americans in Western Massachusetts, In Memory of Susan Freedom, he states that many-perhaps most- early Massachusetts residents of color now lie forgotten in unmarked graves on the periphery of common burying grounds and municipal cemeteries. If they were marked at all, it was often with field stones.

Drinkwater believes these two black women’s graves were once segregated at the edge of the cemetery, before white burials expanded around them. Standing side by side he posits that the younger Sarah Gray served in the same household. Elsewhere in the Bridge Street cemetery, he noted at least a few other gravestones for African Americans, buried several decades later, among their white neighbors. One is for Samuel Blakeman who died in 1879. Another is for Mattie “a Negro” who died in 1862. Far fewer graves are evident than the many people we are coming to know once lived and worked in Northampton. Just as the lives of Northampton’s early black residents were often left out of the written record, so too their deaths.

Sources:

__Massachusetts: a Concise History by Richard D. Brown and Jack Tager. The revised edition was published in 2000 by the University of Massachusetts Press, Amherst.

__Trumbull, James Russell. History of Northampton Massachusetts: From its Settlement in 1654. Volume I. 1898, Volume II. 1902. Northampton.

__Romer, Robert H. Slavery in the Connecticut Valley of Massachusetts. Levellers Press, Florence MA. 2009.

__Warren, Wendy. New England Bound: Slavery and Colonization in Early America. W.W. Norton & Company, New York, London. 2016

__Hardesty, Jared Ross. Black Lives, Native Lands, White Worlds: A History of Slavery in New England. University of Massachusetts Press, Amherst and Boston MA. 2019.

__Carvalho III, Joseph. Black Families in Hampden County, Massachusetts 1650-1865. Revised second edition, 2010. Accessed on academia.edu Oct. 26, 2020.

__Minkema, Kenneth P. ”Jonathan Edward’s Defense of Slavery.” Massachusetts Historical Review, Vol. 4, Race & Slavery (2002), pp.23-59. Massachusetts Historical Society. Courtesy of Historic Northampton.

__Minkema, Kenneth P. “Jonathan Edwards on Slavery and the Slave Trade.” The William and Mary Quarterly, Vol. 54. No. 4 (Oct., 1997), pp. 823-834. Omohondro Institute of Early American History. Courtesy of Historic Northampton

__Harper, Douglass. “Slavery in Massachusetts.” Slavery in the North. Retrieved 2020, Aug 6. http://slavenorth.com/massachusetts.htm.

__Greene, Lorenzo J. The Negro in Colonial New England 1620-1776. Atheneum , New York. edition 1968 of original 1942.

__Piersen, William D. Black Yankees: The Development of an Afro-American Subculture in Eighteenth-Century New England. University of Massachusetts press. Amherst. 1988.

__Gerzina, Gretchen Holbrook. Mr. and Mrs. Prince: How an Extraordinary Eighteenth-Century Family Moved Out of Slavery and Into Legend. HarperCollins Publishers, New York,NY. 2008. My favorite history book, not only local and very readable but illuminating the lives of enslaved blacks and how history is written.

__Sweet, John Wood. Bodies Politic: Negotiating Race in the American North, 1730-1830. University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia PA. 2003.

__Sharpe, Elizabeth and Zeig, Emma Winter. Historic Northampton. Email correspondence Aug-Sep, 2020.

__Bureau of the Census. Bicentennial Edition: Historical Statistics of the United States, Colonial Times to 1970. Part 2, Chapter Z.Series Z 1-19 Estimated Population of American Colonies: 1610-1780. Colonial and Pre-Federal Statistics.

__Stinson, Susan. Spider in a Tree: a novel of the First Great Awakening. Small Beer Press Easthampton MA. 2013.

__Stinson, Susan. Email correspondence Sep. 2020.

__Drinkwater, Bob. In Memory of Susan Freedom: Searching for Gravestones of African Americans in Western Massachusetts. Levellers Press. Amherst MA. 2020.

Thank you Susan. I just have kept reading and reading, digesting, and being prompted by your critique so many months ago.

LikeLike

Wow, thank you for the huge amount of research on this!

LikeLike

I am amazed by this post. I learned so much! But I am most amazed by your research. I can’t imagine the time and energy it took to do all the research, and then put it all together into such an article. Once again, thank you very much for your work.

Sent from my iPhone

>

LikeLiked by 1 person

I am amazed by this pist. I learned so much. I cannot imagine how much time and energy you spent doing all this research, and then putting it all together into this post. Once again, thank you for all your work.

JS

LikeLiked by 1 person