The Valley Women’s Center was at 200 Main Street in Northampton. In 1974 the Center reorganized itself along socialist feminist lines into a union: Valley Women’s Union (VWU). When a coordinating board was formed to represent the various enterprises and action groups* comprising the VWU, Lesbians asked for and were given an at-large seat. While very present in various activities Lesbians did not yet have a formal group, but shortly after getting a seat on the board a Lesbian Issues Discussion Group formed. It met weekly, and grew to include thirty to forty women, mostly lesbians, some of whom hadn’t previously been part of VWU.

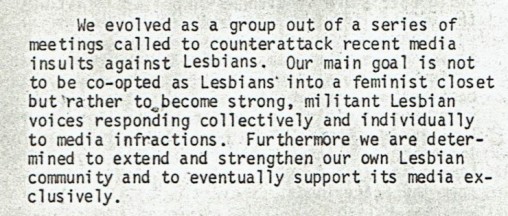

In May of 1974, the CLIT (Collective Lesbian International Terrors) Papers were circulating nationally. Initially, the CLIT Collective called for lesbians to withhold their energy from straight media, which continued to define and co-opt lesbians. The Collective advocated the creation of a separate Lesbian media. The idea was further expanded to mean withdrawing from the straight world as much as possible, including straight feminists, and creating a separate Lesbian community and culture.

The CLIT Papers, by a NYC group, caused a furor in feminist communities from coast to coast, including the feminist community in Northampton. They resonated particularly with Lesbians such as myself, who had devoted a lot of energy to women’s issues, but whose needs as lesbians were largely unrecognized. As a result of this new thinking some VWU Lesbians wrote a position paper asking for separate space at 200 Main Street. They began scheduling Lesbian-only events in the third-floor general meeting room, calling it “Lesbian Gardens.”

Increasing numbers of Lesbians began to identify themselves with this radical thinking and literally spelled it out. The different usage of lesbian (lower case) as a sexual identity and Lesbian (capitalized) as a political identity began to appear. If you see it here it is as carefully deliberate reflection of how it began to appear in local Lesbian writing and publications starting in 1974.

While still a student at UMass I helped start Everywoman’s Center, housed initially in 1972 in one large room in Munson Annex. In the beginning we pretty much invented our jobs, even as volunteers, and I wound up coordinating publications (a newsletter) and educational programming. We had inherited a workshop program for women designed to encourage continuing education, Project S.E.L.F. and in one of the first series Cindy Shamban and I co-facilitated a four week workshop in 1972 called “the Woman-Identified Woman.” The topic and title came from a 1970 position paper by NYC Radicalesbians which I found and brought back from the second Christopher Street Liberation March. This may have been the first such offering in the Valley.

After I graduated from UMass I continued to work at Everywoman’s Center as paid part time staff with no benefits. The eight week long workshop program was one of my main responsibilities and continued to be for several years, growing to an attendance of 350-400 women enrolled every semester, half of them non-students. Every semester I was able to include at least one with lesbian focus. The most popular was Julia Demmin’s “Lesbians in Literature,” which she offered numerous times, often with her partner Nancy Schroeder.

1975 began with the last program I coordinated for Everywoman’s Center, what may have been the largest gathering up to that time of Valley women, a week long University (UMass) Women’s Conference in Amherst attended by over 700 students, staff, faculty and community women. It also included the largest gathering of lesbians, more than sixty, who attended one or more of the three lesbian workshops.

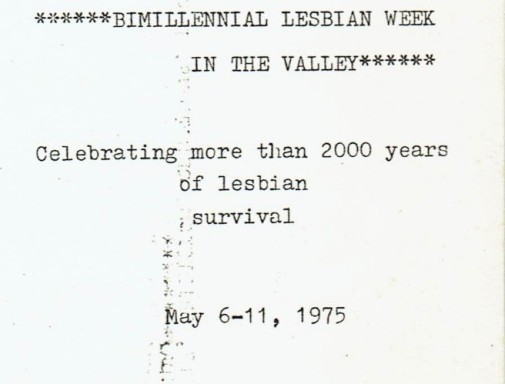

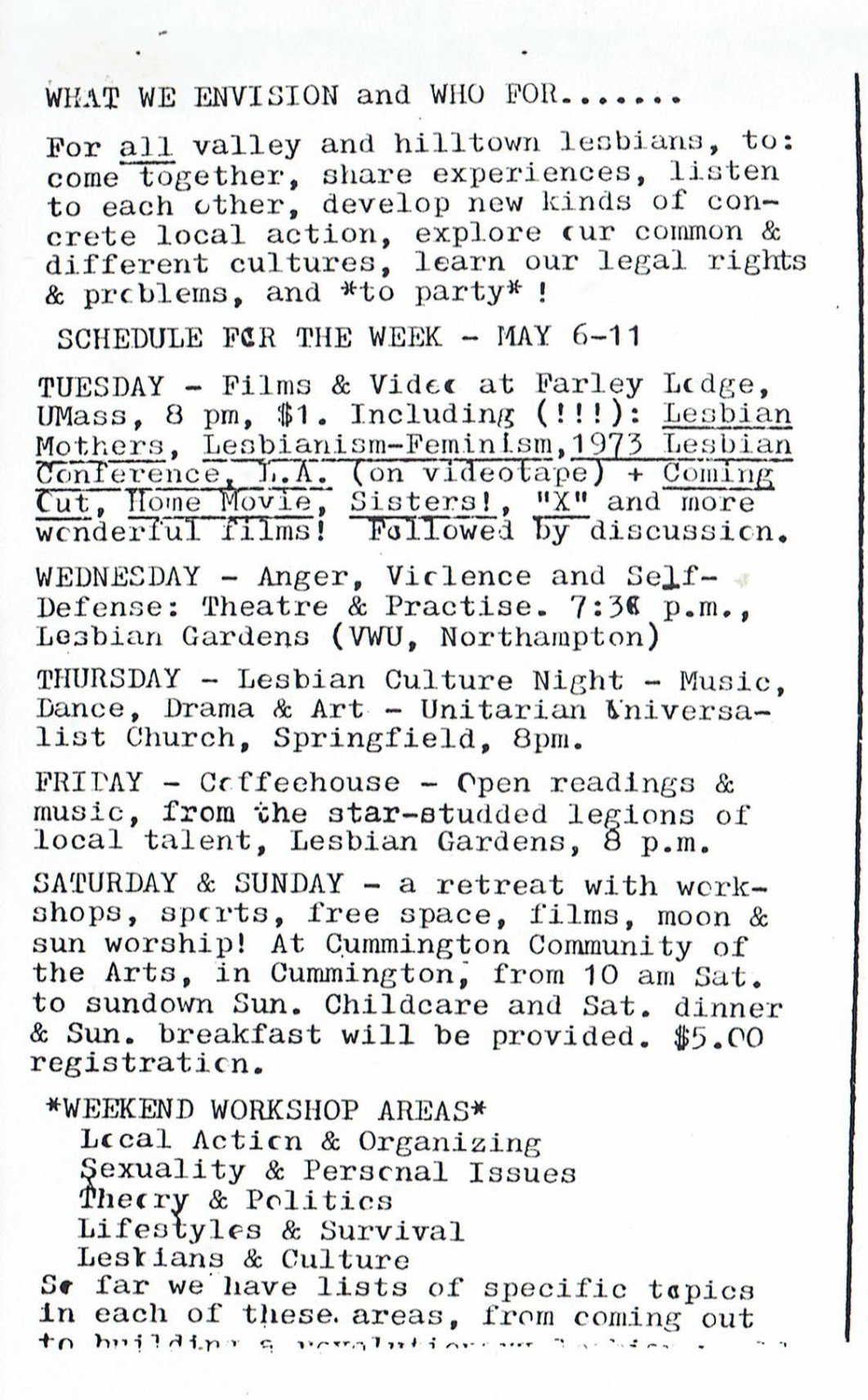

At the end of the conference, energized by this response, planning began for a similar conference for Lesbians in a collaboration of the UMass Gay Women’s Caucus; Lesbian Gardens; and UMass, Springfield, and Northampton women’s centers. The BiMillenial Lesbian Week was held in May 1975 with events in Springfield, Amherst and Northampton, culminating in a weekend retreat in Cummington which I attended. “BiMillenial” referred to two thousand years of Lesbian culture since Sappho.

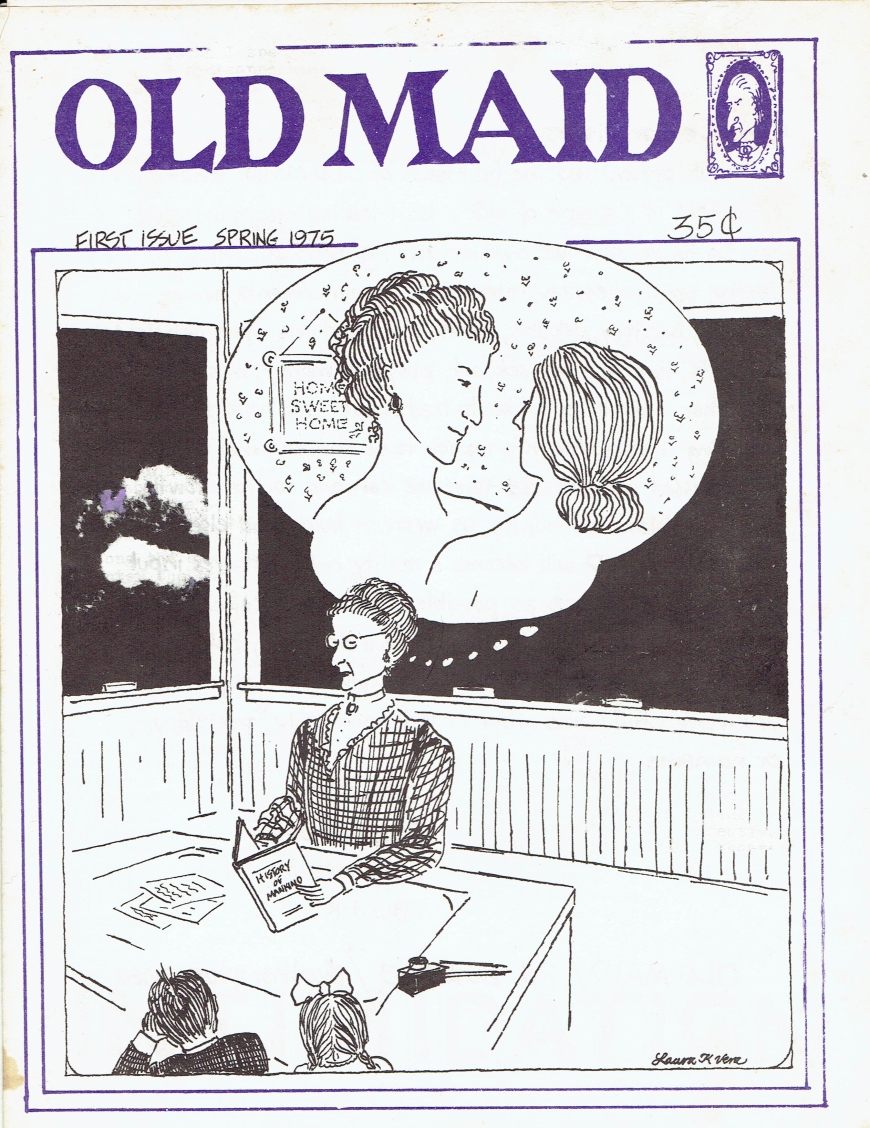

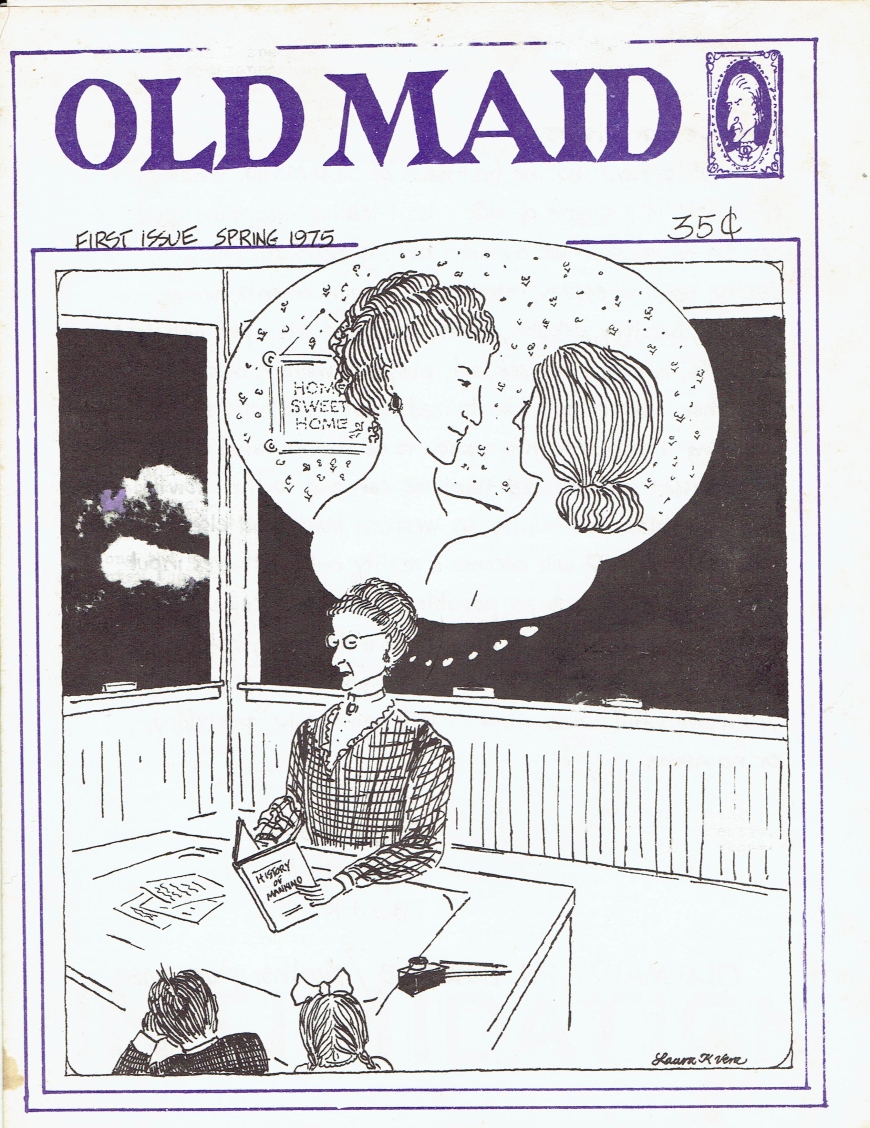

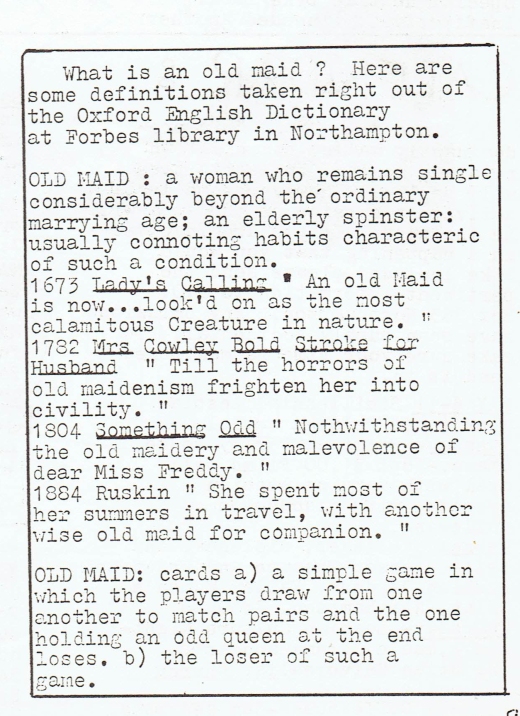

This happening, as we used to say, was advertised in Lesbian Gardens’ first publication. Old Maid: the Lesbian Magazine. The BiMillennial Lesbian Week marked the beginning of a proliferation of Lesbian activities. An increasing number of these took place at Lesbian Gardens, including a Saturday Night Coffeehouse with music by Lou Crimmins and other local musicians, the showing of the first U.S. Lesbian-made films, the formation of the Magical Lesbian Playgroup (a mother-daughter group?) , and the convening of the first Skills Exchanges and Winter Solstice Celebrations. Lesbian Gardens also provided space for the initial meetings of what became new enterprises; the women’s restaurant project, the women’s self-defense and karate school, and the Lesbian back to the land movement.

In the late Fall of 1975, the Lesbians coordinating the use of Lesbian Gardens proclaimed it to be 24-hour Lesbian space, contentiously precluding its use by straight VWU feminists. The Sweet Coming Bookstore (more like a bookshelf) was established there to sell the scant but growing number of Lesbian publications from around the country: the first mimeographed and stapled issues of Lesbian Connection, coming out stories, health information, news and discussions by and about Lesbians. A Lesbian distributor, Old Lady Blue Jeans, also began to have locally created products for sale there. An album by local musician Linda Shear, as well as some coloring pages by me as Great Hera’s Incunabula, were listed in Old Lady Blue Jeans’ catalog.

The BiMillennial Lesbian Week collaboration between Northampton, Springfield, Amherst, and hilltown Lesbians provided a supportive base for a Lesbian cultural flowering and new level of feminist activism over the next decade. A significant portion of it was to happen in Northampton, which seemed to have a population explosion of newly-out lesbians. Though this Valley Lesbian Movement was to be fraught with struggle, both internal and external, its very depth and breadth was to exhibit a maturity that reflected the same pains, questions, doubts, and resolve experienced across Lesbian Nation.

*Valley Women’s Union initial coordinating board represented Mother Jones Press, Women’s Film Coop, Employment, Staffing, Newsletter, Childcare, Study and Research work groups.

SOURCES:

__[Raymond}, Kaymarion and Letalien, Jacqueline E., editors. The Valley Women’s Movement: A Herstorical Chronology 1968-1978. Northampton, Ceres Inc. 1978.

__Collective Lesbian International Terrors. “CLIT Papers, Part One and Two” and OOB Staff editorial. Off Our Backs. Washington DC. May and July 1974.

__Conference Evaluation Committee. “1975 University Women’s Conference January 21-25: Report and Evaluation”. EWC, UMass Amherst Mar. 1975. I coordinated this conference and wrote parts of the evaluation including that about lesbians.

__Old Maid: A lesbian magazine. Northampton. Spring 1975.

__Old South St. Study Group. “Analysis of a Lesbian Community-Part One” and “-Part Two.” Lesbian Connection [E. Lansing MI]. Jul.1977.

__Kraft, Stephanie. “BiMillenial Celebration: 2000 Years From Sappho.” Valley Advocate. 30 Apr. 1975.

__[Raymond],Kaymarion. “The Cloning of Old Lady Blue Jeans.” Sharer’s Notes #3. Great Hera’s Incunabula. Nov. 1975.

_________. “Valley Women’s History”, Meeting notes. Common Womon Club, Northampton. 15 Apr. 1980.