On a hot day with big blue sky when I was nineteen and an Army private, I took the city bus from Fort Sam to downtown San Antonio for the first time. After a tourist stop at the Alamo, I just walked around until I came upon an adult bookstore. Hoping to find some clue to gay women’s life in 1965 Texas, or at least a copy of the Ladder, I hesitantly scanned the display aisles, skirting men looking at I-didn’t- want-to-know-what.

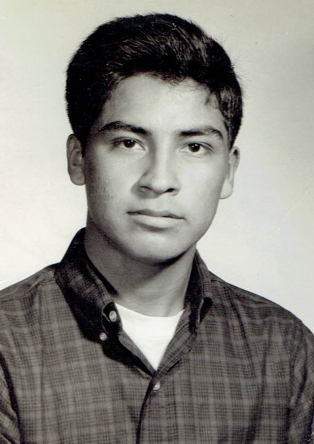

Near one line of magazine racks, a young Latino caught my eye. Looking pointedly at my short hair and the wedding band on my left hand, he said hello and walked with me out of the store. Vincente, a high school student, befriended me then and there.

With the connivance of his Army nurse boyfriend Fred, who owned a car, Vincente began to pick me up at the WAC barracks for dates on the weekends. The story was that we were going horseback riding. That was the only excuse I could think of to leave the post wearing pants instead of the required WAC clothing standard skirt.

We actually did go to “the country,” because that was what everyone called the gay bar outside the city limits. The bar was housed in a large single-story building surrounded by an even larger gravel parking lot in the middle of a very dark nowhere. Daylight might have revealed cattle pasture and scrub, but I never saw it during the day. The bar was mostly dance floor surrounded by tables. It was dimly lit and smoke filled. Vincente called me his auntie and taught me to dance to whatever was on the jukebox. This is where I came out, beyond that earlier declaration to myself and a few individuals, as a gay woman and butch. Doing the Jerk and the sounds of Motown became embedded forever, by hormones, in my DNA.

The inside of a queer bar was exposed to the world after the Pulse Nightclub massacre in Orlando Florida June 12, 2016. Pictures of the physical space, bar, and dance floor were flashed through newscasts and social media. These were also pictures of a kind of emotional space created by the people who danced there. In this case, those people were mostly young, male Latinx drawn from one of the largest Puerto Rican communities stateside.

In the days that followed the mass shooting, the importance of bars as central to queer culture was repeatedly stated in many different ways by that local queer community and others around the country. Queer bars were compared, even, to going to church. This centrality of bars to queer culture seemed primary even as Orlando’s GLBT community center stepped in to offer information, support, and services to the victims’ family and friends. The community center also kept the larger community informed about what was happening and needed.

In local discussion over the next few months, I was reminded that not everyone came/comes out in bars. There was a period in Northampton’s history when the Women’s Movement and then the Lesbianfeminist and Lesbian separatist communities offered an alternative to the bars of Springfield and Chicopee. The spaces – both physical and emotional – that these movements provided were where I came further out politically. They shaped the identities of at least one generation of Lesbians, those who once knew why the word was capitalized.

The height of these movements, however, had a relatively brief period locally. While there were many interest groups, events, and a few businesses during that time, spaces that actually functioned as dedicated meeting and activity places were sparse and limited in their functions. Lesbian Gardens existed as part of the Valley Women’s Union on the third floor of 200 Main Street from 1975 until 1976. The whole group left the space when they were unable to meet a steep rent increase. The Common Womon Club opened on Masonic Street the next year, 1977. They provided a lesbian community dining, meeting, and communication space. They also sponsored many events in larger venues, including dances. The Club closed six years later, largely due to its unprofitability and reliance on an ever-changing collective of underpaid staff.

Only institutionally-supported centers seem to last in the Valley. In Northampton, this meant that Smith College housed a Lesbian Alliance for many years. (The name of the group given space has frequently changed.) Local area efforts in 1990 to open a GLBT community center failed, in large part because of the relatively high rental cost of space in the downtown.

This brief period since the 1970s of new spaces emerging outside the gay bars reflected a national trend. The disappearance of those new spaces is also reflected across the country, though a few spaces with the largest supporting population have lingered on. Most recently, there has been increasing conversation about the disappearance of lesbian space prompted by the closing of the Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival, which was an annual national gathering for 40 years.

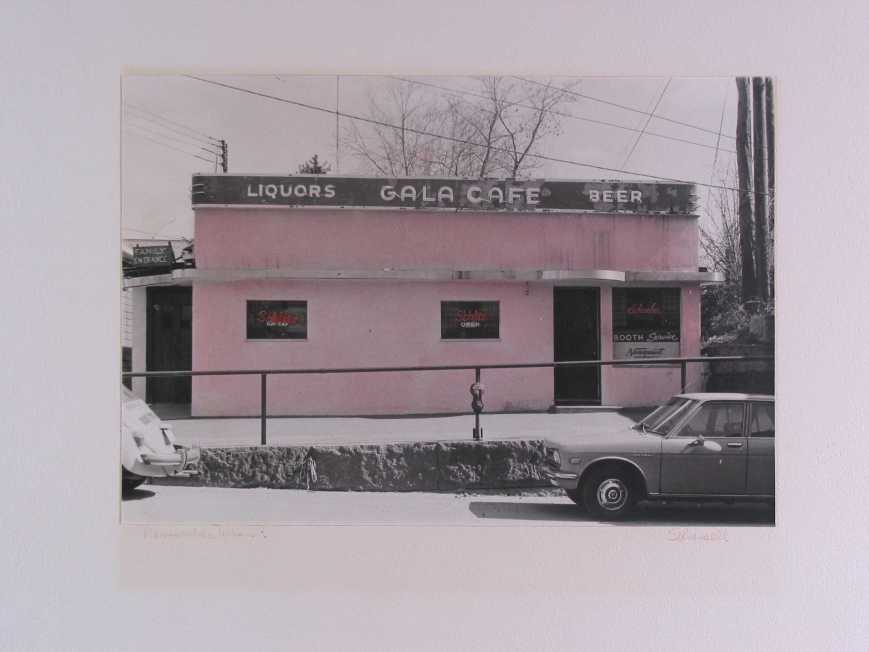

The national discussion of disappearing women’s space also includes women’s (lesbian) bars. Northampton also has a history of bars that grew alongside and then largely outlived that of the Lesbian, separatist and feminist, spaces. Even as Lesbian Gardens was being organized by Separatists, lesbians found a way to dance in the backrooms at the straight bars Gala and Zelda’s in 1975. Other than that, lesbians relied on sporadically sponsored women’s dances elsewhere. Lesbians also followed the women’s bands that played the straight club circuit in the Valley and later attended lesbian DJ’ed nights in straight spaces.

It was not until 1987 that Northampton had its own LGBT bar, owned and run by lesbians: The North Star on West Street lasted eight years. Competition came from Pearl Street, a straight dance club which began to hold a gay night. In 1996, a group bought out the North Star and opened the Grotto in that space, which lasted through 2001, perhaps. I have heard mention of a Club Metro, but have no information on it. The latest and the longest surviving LGBTQ bar has been Diva’s, opened in 2001 on Pleasant Street, but is announcing its “last” events this autumn of 2016.

The historical pattern seems to suggest there is enough business to support one bar establishment in Northampton if it makes an effort to cater to the wide variety people under the queer (or not) umbrella. It also suggests that a bar is more central to queer culture and community in Northampton than any of the other physical spaces that have come and gone.

A red light was mounted on the wall behind the bar in that 1965 Texas gay club called the Country. When it flashed on and off whoever was on the dance floor scurried to switch to dancing with partners of the opposite sex or sat down. Others stopped smooching and groping as the local police came in the door and did their nightly walk-through looking for illegal behavior.

Out in the parking lot, military police crunched across the gravel, writing down license plate numbers of those with the mandated military stickers. The Country was off-limits to military personnel, a fact listed outside the orderly rooms of every barracks in the area. If one could sort out the names of establishments that were just violent, this list was a de facto gay guide. Being discovered at the Country could lead to further investigation and a dishonorable discharge or coercion to inform and entrap others. Gay women in particular were disproportionately discharged for homosexuality in almost annual salacious witch hunts, which I and many of my WAC friends endured.

Fifty years later things may have appeared to change, but it is apparent from Pulse nightclub massacre news accounts that some of the victims and/or their families did not want it known that they were in a queer bar. While the law might now at least superficially protect them as brown and queer people, the cultural attitudes that spawned the killer did not. There was and still is a danger in being queer, out, and out with others.

This danger is also part of Northampton’s history. As lesbians found each other in the town’s bars they became the target of rape and assault. Coming far enough out of the closet to march as a community with allies en masse down Main Street brought phone stalking and threats of murder and arson. It took a concerted political struggle with Northampton’s government, police, and press to begin to change the environment.

There is no making sense of the mass murder at the queer nightclub in Orlando, but a pause has allowed me to re-see, through my anger and grief, the importance of queer cultural meeting spaces for dancing and celebration. These centers of affirmation are an essential part of the LGBTQ story past and present, including Northampton’s. Over the coming months, I will be sharing accounts in this blog of much of what has just been briefly mentioned. Meantime keep on dancing.

Great stuff – Kaymarion! Love reading your work. Love that you are preserving our history. Thanks.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wonderful. Even though this herstory of your is known to me, your reflections on Lesbian spaces are awesome insightful.

Love,

Laura

LikeLiked by 1 person